Issue 4/2010 - Politisches Design

Political design in Asia and Europe

On the background and sections of the exhibition »Re-Designing the East«

With projects such as »Postcapital«1 (2008/2009), »Territories of the In/Human«2 (2010) and currently »Re-Designing the East – Political Design in Europe and Asia«3, the Württembergischer Kunstverein endeavours to take a closer look at the many facets of social, political, economic and cultural upheavals over the last 20 years from a range of different angles. Since the early 1990s, if indeed not before – in the course of the disintegration of the Soviet Union and the so-called East Bloc states, and the emergence of unbridled capitalism coupled with the rapid development of mobility, information and communication technologies – the world order that previously held sway experienced a radical and lasting shift. Despite all the re-emergent forms of these older notions of East and West defined in terms of ideology (for example the flaring up of new Cold War rhetoric in relations between North and South Korea), these concepts have grown obsolete or have shifted their focus to antagonistic discourses between the Christian and Islamic world. In the latter context, however, the newly identified enemy of the »West«, Islamic fundamentalism, acts neither in an anti-capitalist manner nor, as some like to claim, archaically, but instead dovetails perfectly with the anti-democratic implications of capitalism..

In the distant – from a Eurocentric perspective –»East«, China has long assumed global importance in the economic realm, as have countries such as South Korea, Thailand and India. Erstwhile cartographies, in which the »West« functioned as the centre and the »rest« was viewed as peripheral, have been replaced by mappings, which, depending on your perspective, could be described as multi-centric or multi-peripheral, even if »Western« societies have not fully absorbed the implications of this yet. The latter have long ceased to be the main protagonists in the wide-reaching, bifurcating struggle for status within the shifting world order, which perhaps is not so much »post-Communist« but rather »post-capitalist« – if we do not take »post-capitalism« to signify the end or the defeat of capitalism, but rather changes in its structures and modes of functioning: in the absence of its former »dance partner«, socialism (Ivan de la Nuez4), within the context of the global competition to achieve »accumulation by expropriation« (David Harvey) and as a set of instruments for a knowledge society based on immaterial assets.

»Re-Designing the East« was intentionally chosen as a title that admits its own helplessness in the face of geopolitical categorisations that have long become questionable and which it is so difficult to shake off. The »West«, the »East«, the »centre«, the »periphery« are categories that remain tenable only when viewed through the prism of the slippage of their former meanings, yet through which at the same time we cling to the old ideological templates – either reinforcing these or affirming the differences between former and current usage – as if holding tight to a compass.

»Re-Designing the East« could however also be understood as a provocative metaphor of the redesign, accompanied by numerous highly complex conflicts, of the former »peripheries« of the »West«, a process that it would be overly reductionist to view as merely a straightforward »Westernisation« of those peripheries and one that profoundly changes what we still generally understand by the »West«. These changes lie in the direction of a post-capitalist, multi-centric/multi-peripheral society, whose conflicts perhaps constitute the smallest and greatest common denominator and in the question of what kind of world we wish to live in, who participates in re-design processes and who does not, who benefits from these and who is left out in the cold.

The point of departure for »Re-Designing the East« was an exploration of the question of the role that critical, actively resistant design practices have played and continue to play in the struggle to achieve political, social, economic, ecological and cultural re-design in Europe and Asia. In six sections, conceived by six curators5, the exhibition focused attention both on highly distinctive design positions and on the wide range of spatially and temporally specific contexts, which are set in an open relationship to each other. Ultimately six statements, whose substantive and temporal coordinates overlap around the edges and at the same time point in different directions, gave expression to the rough framework sketched out at the start of the project, taking 1980s political design, which played a decisive part in shaping the process of change in Eastern Europe – specifically in Poland, Hungary and former Czechoslovakia – and contrasting this with current critical design practices in Asia, which explore the socio-political conflicts in Thailand, South Korea and India.

The East-East axis

Nikolett Erros and János Sugár note that the tradition of political design in Hungary since 1968 is essentially rooted in not terribly innovative models and imitations, which they ascribe inter alia to the lack of a revolution, a radical sea-change and to the failure to engage in grappling with the recent past.6 For the exhibition they present a mise-en-scène of a laboratory of imitation, which addresses the question of the visual representation of radical changes, exemplified in terms of the failed Hungarian revolution in 1956. The laboratory presents documentation on the proposals for memorials from two freedom fighters from 1956, which were never implemented: István Angyal’s proposal to dedicate a large cobblestone to the »anonymous crowd« of the 1956 revolution and Gergely Pongrátz’ idea of turning a pair of boots into a monument to the revolution, namely the remains of a gigantic Stalin statue, destroyed by precisely that anonymous crowd. Angyal’s idea is also displayed in the form of a polystyrene mock-up.

Working through the legacy of totalitarian regimes, a process Nikolett and Sugár feel is lacking in Hungary, is always particularly difficult in the case of figures once numbered among dissident protagonists and subsequently accused of having been spies. Curator Tomáš Pospiszyl turns his attention to one such figure: dissident designer Joska Skalník. In the 1970s and 1980s he supported various independent cultural initiatives in what was then Czechoslovakia as a graphic artist, set designer and organiser: the projects included the Jazz Section, the Actors’ Club and the mini salon he initated.7 For the exhibition Pospiszyl, working in conjunction with designer Jan Matoušek (Grafikstudio Laboratory), developed a video documentation reflecting on the work of the ambiguous designer.

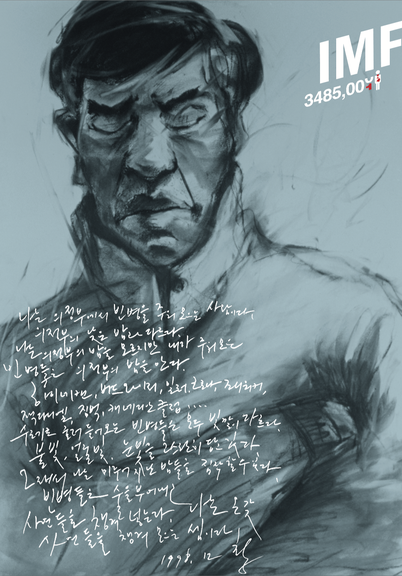

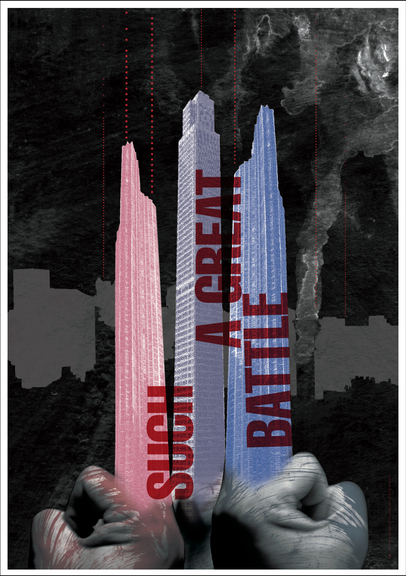

The section devised by Nathalie Boseul Shin, working with design group Activism of Graphic Imagination and artist and activist Noh Suntag, addresses current socio-political conflicts in South Korea in the context of a broad historical background, reaching back to the foundation of the Republic of Korea in 1948, and thus to the time when North Korea and South Korea were first divided. Hardliner Lee Myung-bak8, elected President in 2008 has increasingly deployed the National Security Act, which also dates from that era, viewing it as a legitimate instrument to repress left-wing positions. The newly resurgent Cold War rhetoric came to a peak around the sinking of the warship Cheonan in March 2010, allegedly by North Korea. At the same time the excrescences of unbridled turbo-capitalism, directed by a small number of family-controlled corporate groups (jaebols), came to a head in various mega-projects for urban and rural redesigns. For example, the Four Rivers Project envisages radically intervening in the course of the country’s four main rivers. The wholesale remodelling of city districts, such as Yongsan (Seoul), which includes plans for the luxurious Yongsan Business District and Daniel Liebeskind’s Dream Hub, go hand-in-hand with expropriation of enormous swathes of residential areas and infrastructure owned by medium-sized firms. Artists like Noh Suntag and designers or design groups such as Activism of Graphic Imagination are part of a broad network of resistance to these government policies.

South Korea and Poland share a link in the form of the 1980 uprisings in Gwangju and Gdansk: the Solidarność logo in particular has become branded into global collective memory.9 The Wyspa Art Institute in Gdansk focuses on the shifting uses and perceptions of the logo designed by Jerzy Janiszewski have shifted, for it has moved from being a symbol of social unity to a brand, from a gift to the Polish people to a bone of contention, both commercially and politically, in arguments over the right to exploit the symbol. In addition to various adaptations of the logo by political designers, for example in the context of the 1989 elections in Poland, the exhibition also shows works by artists that reflect on the various modes of dealing with the logo.

Whereas the question of the meaning and purpose of copyright protection of a collective symbol arises in the context of the Solidarność logo10, the network of designers, writers and architects, Design & People, presented by Sethu Das stands for a »copyleft« attitude in the design world. The network, founded by Das in 2003 in Kerala, supports independent social, political, humanitarian, ecological and education projects, and works with movements such as Friends of Tibet or the Global Gandhian Movement for Swaraj. At the same time it sees its role as that of an agent of open critical knowledge production. Design & People draws the inspiration for its Open Design & Information philosophy from Mahatma Gandhi’s idea of self-administration and self-determination (swaraj), as implemented in 1909 in Hind Swaraj. In a design approach »swaraj« signifies both a struggle for political self-determination and a design practice that moves away from self-interest and the Western concept of individualised creative forms of expression.

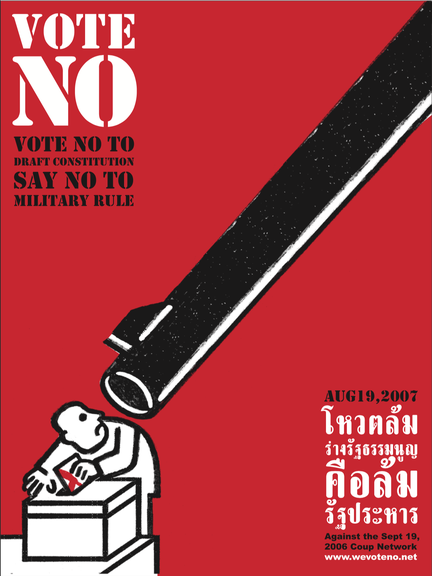

In Thailand an ambivalent struggle for societal influence is currently underway, partly because the semi-divine king is by now rather elderly. Invoking democracy, a diverse range of groups are struggling to acquire greater power; a struggle, which, in a country »whose people rely more on the evidence of their senses than on literature«11, is being conducted to a significant extent on the visual plane, whilst at the same time being subject to growing censorship. The exhibition section curated by Keiko Sei presents a selection of works by Thai designer Pracha Suveeranont, who in 2007 also developed a campaign calling for an electoral boycott of the new constitution devised by the military.

The aim of the exhibition, as in previous projects organised by the Württembergischer Kunstverein,12 is to explore the model of multi-perspective, process-based curating. »Re-Designing the East« has generated a highly heterogeneous, diverging structure, branching out in multiple directions and highlighting the possibilities, limits and ambivalence of design positions focussed on resistance and the struggle for political co-determination.

Translated by Helen Ferguson

1 Postcapital. Archive 1989–2001. Ein Kunstprojekt von Daniel García Andújar/Technologies To The People, c.f. http://www.wkv-stuttgart.de/programm/2008/ausstellungen/postcapital; http://www.postcapital.org; c.f. Yvonne Volkart, Das Archiv als Ort der Versammlung, in: springerin 2/2009.

2 http://www.wkv-stuttgart.de/programm/2010/ausstellungen/territorien-des

3 http://www.wkv-stuttgart.de/programm/2010/ausstellungen/re-designing-the-east

4 http://www.bcn.cat/virreinacentredelaimatge/english/02060411.htm

5 Maks Bochenek (Gdansk), Sethu Das (Keralla), Nikolett Eross (Budapest), Tomas Pospiszyl (Prague), Keiko Sei (Bangkok) and Nathalie Boseul Shin (Seoul).

6 C.f. the essay by Keiko Sei in this edition.

7 C.f. the essay by Tomáš Pospiszyl in this edition.

8 Also ironically dubbed »Two Megabytes« by his critics [II (Lee) M(yung) B(ak)].

9 On this point, see the essay by Keiko Sei in this edition.

10 Protection which, as we know, aims to protect rights holders, rather than primarily protecting the creators of works.

11 Keiko Sei, Curators’ statement.

12 For example in the context of »On Difference« (2005/06) and »Subversive Praktiken« (2009). C.f. On Difference #3. Raumpolitiken, (eds.) Iris Dressler and Hans D. Christ. Württembergischer Kunstverein Stuttgart 2007; Subversive Praktiken. Kunst unter Bedingungen politischer Repression. 60er–80er/Südamerika/Europa, (eds.) Iris Dressler and Hans D. Christ. Württembergischer Kunstverein Stuttgart, Ostfildern 2010.