First, an admission: I am one of them. I have 698 »friends« on Facebook, 2,657 »followers« on Twitter, 820 have added me to their »circles« on Google+; I can barely count the number of other platforms on which I am registered. This is despite the fact that I don’t go about the business in an arbitrary way. I only confirm contacts when a name means something to me, and I don’t confuse my »friends« with those people that I call »Freunde« in exclusive German usage.

»Am I accusing all those hundreds of millions of users of social networking sites of reducing themselves in order to be able to use those services?« Yes, the information scientist and artist Jaron Lanier writes in »You Are Not a Gadget«1 , because the concept of friendship as understood by someone with as many friends as that must inevitably be a blunted one. According to Lanier, not even reflection can help once we have swallowed the bait: what may feel like making contacts to users, he says, is mostly self-exploitative target group qualification for the real customers of the social networks – commercial interests.

When is a friendship a friendship ? There have been countless and inevitable attempts to quantify the concept ; they fill philosophical essays and poetry albums, but there is always something unqualifiable left over : why is he my friend, why is she my best friend ? In social networks, this problem is apparently solved. I click on »See Friendship« and Facebook gives the answer. D. and I have been connected since May 2007. We have 21 »friends« in common, have gone to a dozen events together and can be seen together on even more pictures, the database tells us. It gives no answer as to why and is not interested in whether we actually go to the events that we say we will visit or whether we are really in the pictures where we are tagged. If nothing seems to have been left in doubt, there is nothing more to ask. The databases of the social networks give us a model for describing our friendship.

But this model is not a good one, Lanier argues. A pioneer of virtual reality, he has himself designed immersive worlds in which people meet one another as a controlled data model. »When we ask people to live their lives through our models, we are potentially reducing life itself. How can we ever know what we are losing?«2 To put the question another way: if the unqualifiable remainder of friendship does not appear in the model – even as a gap – will we soon still know that something is missing?

The official story of the misunderstood Web 1.0 that only finally found itself in the version 2.0 has a solid technological basis: dynamic websites with a high interactive potential, databases instead of manually generated layouts and content, tools for recommendations and forwarding, interfaces for data access, and analyses of all data occurrences to proclaim the proclivities (aka wisdom) of the »crowd«. However, on its own, Web 2.0 does not explain the transformation of relationships into the »social web«. Even before Facebook, people networking had become a widespread phenomenon, as individual e-mail addresses provided precisely what was needed: the specific addressability of people. Unlike letters, e-mails do not end up in the wrong letterbox by mistake and are seldom used collectively. The global network of user relationships existed latently in the users’ address books and was kept up to date under their control according to need. Now Web 2.0 companies are harvesting the yield of this network. Are you amazed by how accurate the friend proposals are that Facebook sends you even before you register? It is enough for just a few people to use the option of connecting their online address book with the platform – the reconstruction of relationships using e-mail contacts produces outstanding results and allows it to constantly extend the personal network (»People You May Know«) on the side. After Wave and Buzz, Google is now trying for a third time to wrest the relationship monopoly from Facebook – this time with Google+, mostly by making imperturbable use of Google Mail users’ address books. The result: 25 million members in just five weeks.

Unlike with letters, and even unlike a pure e-mail service (as which Google Mail cannot be considered), the network of relationships in social networks is not shaped, developed, analysed and evaluated under the guidance of the users, but under that of the platform providers. The users just feed the network, improve it, make its results saleable and finally borrow it back to gain access to their »friends«.

But Lanier’s critique does not start with the social networks. The reduction he warns about starts whenever aspects of people are subjected to the limiting rules that go to make databases administrable. According to his sombre prognosis, for people who interact with the world via databases, the database will at some stage become the world and its reductive categories will become the accepted illusion.

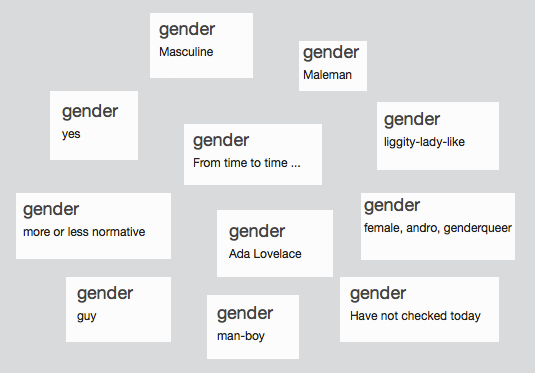

In practice, this means: the more database-friendly drop-down menus and click-on options, the more a person is spoon-fed; the more space there is for free text, the more space there is for personality, or even authorship. »If you read something written by someone who used the term >single< in a custom-composed, unique sentence, you will inevitably get a first whiff of the subtle experience of the author, something you would not get from a multiple-choice database.«3 The hegemonic gender discourse has its equivalent in the Either-Or option; domination is technically ensured by what Lanier calls »lock-in«: a complication of software architectures that makes it increasingly difficult to depart from created structures. Either-Or options are easy to administer – fields for free text provoke »human errors« and lead to a direct increase in the number of unique entries. We do not forget the commercial interest in filtering its target group on gender lines, but even without this it is enough for individual processes of a complex data architecture to encode gender in binary form (for example, direct marketing systems with their insistence on forms of personal address such as »Mr/Ms«) to make any change favouring personal truth unlikely: »Computers can take your ideas and throw them back at you in a more rigid form, forcing you to live within that rigidity unless you resist with significant force.«4 The Ruby developer Sarah Mei showed some resistance to this in autumn 2010: she turn the drop-down menu »blank, male, female« of the social network diaspora5 into a text field. The entries made by users regarding »Gender« display Lanier’s »whiff of authorship«: Masculine/Maleman/liggity-lady-like/Ada Lovelace/more or less normative/female, andro, genderqueer/have not checked today.

Mei and Diaspora, the decentral network that wants to give users back the control over their data, are working towards the humanistic praxis of software development called for by Lanier: a use of technology in the service of people’s development instead of dividing them up into fragments that can be exploited to the maximum and that only provide information in extreme quantities, as Lanier claims is the case with Web 2.0. But: despite constant praise, Diaspora is still a platform that is used only by a few people. Why? Their »friends« are all over at Facebook, Twitter, Google+. There, the »network effect«, which gives the participants of a network better and better networking opportunities as it grows, is in operation. Better technology and a more humanistic approach are weak arguments in comparison. What can be done? In a similar vein to Günther Anders, who proposed moral, spiritual exercises to reaffirm ourselves in our relationship to the devices of the »proportio humana«, but more concretely, Lanier comes up with a list of suggestions such as: »Create a website that expresses something about who you are that won’t fit into the template available to you on a social networking site.«6 Some may remember: the early Web was full of sites like this. Colourful backgrounds, coloured fonts, blinking text, animations that followed the cursor. The websites exhibited what someone had learnt in the way of HTML tags and scripts. Although it didn’t always look good, for Lanier it has the »flavour of personhood«.

The idea of such exercises is good – a return to the practice of the 1990s is not very likely as long as hand-encoded websites are not in a position to generate the social background noise that hums ceaselessly on the monopolised social web, signalising: »You are not alone.« Whether it is shaped by others or not: the network reacts. That is better than television.

Translated by Timothy Jones

1 Jaron Lanier, You Are Not a Gadget: A Manifesto. New York 2010, p. 53.

2 Lanier, You Are Not a Gadget, p. 70.

3 Ibid., p. 52.

4 Ibid., p. 134

5 www.joindiaspora.com

6 Lanier, You Are Not a Gadget, p. 21.