Issue 2/2012 - Bleibender Wert?

Values without trust

How Precarious Work Is Shifting Social and Cultural Paradigms

[b]Precarious Fluidity[/b]

Precarious work is the layout of the post–Fordist era. Fordism was »characterized by the mass production of homogeneous, standardized goods for a mass market« and post–Fordism saw »a shift of emphasis within the organization of labour to the immaterial production of information and services and to continuous flexibility« (Seijdel 2009: 4) As post–Fordism reflects a different social and economical value system it's mainstays may be listed as »physical and mental mobility, creativity, labour as potential, communication and virtuosity« (Seijdel 2009: 4)

Precarious work means fluidity. ›Temporarity‹ becomes the main tenet. Precarious working conditions are not something new. It is a gift of the post–Fordist era, and a type of work we are all accustomed to. Yet, there is something different today. Post–fordism is generally dated back to 1970s. The ›differance‹ is, today, we all feel like we are living in the kingdom of Precariousland. It is so dominating. The realm of precarious work is a jungle full of unpredictable and insecure elements. Not only labor markets but also products are more and more individualised. An iphone, for example, is not in itself the end product. It is a platform and it is up to you to create an end product with selected softwares and applications. Design and aesthetics rule. Life is always based on self–discipline on both the production end and consumption end.

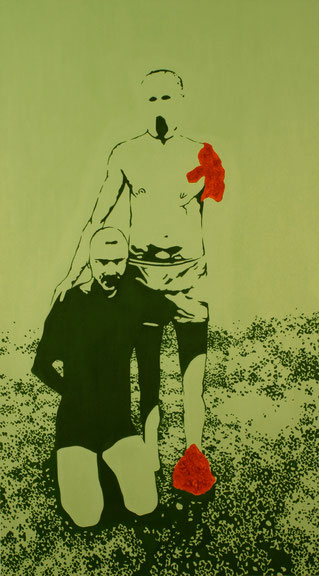

What I want to stress is not that we are living in a terrible, terrible precarious age and that we are all its victims, suffering. Instead I want to highlight two points: a) values are shifting in the precarious age in such a way that it is not that easy to take sides. Power relations in the precarious age resemble sadomasochistic power plays; but the key ingredient is missing: trust. This is The Catch 22 of precariousness. There can be no sadomasochistic power play without trust – yet precarity is claimed to be so by all participating actors.

Rape, for example, as we all know, is not a game, but there may be ›rape play‹ in a sadomasochistic relationship. You can of course, rape someone and then try to convince this person and others that what happened was actually a ›rape play‹. That would be a Fordist manipulation. But in the precarious age, you rape someone, and this person tries to convince you and herself that it was actually a rape play! You may argue that simply because this way it is more prestigious. And in the times of permanent fragility, traditional rape seems so hard to get! There lies the complexity of the post–Fordist manipulation.

As we said before, a sadomasoshistic play is only possible if there is trust. I can order you to handcuff and then whip me and make me beg for hours. You can do the same. But we need to trust each other for that. Otherwise, there comes the atmosphere of »Basic Instinct«, the movie. Which means, precarious work is a safeword that is not safe. Actually the word 'precarity' comes from the Latin word »precare«, which means to beg. And according to Webster’s dictionary »one of the meanings of precarious is ›depending on the will or pleasure of another‹, in other words to possess something that is liable to be withdrawn at any moment.« (Oudenampsen 2009: 119)

[b]Power Relations and Power Plays[/b]

Safewords are widely used in sadomasochistic power plays. A safeword is described as a word (usually irrelevant and strange in the context of the sexual situation) agreed by the participating parties to cease the activity. This is so that the submissive partners can say »stop« and »no« as often as they want during the session and use the safeword when they actually mean it. Because saying no and not meaning it is itself a pleasure while saying a safeword, for example »cherry« and meaning »stop« is the symbol of feeling safe in a trustful environment.

To get closer to the psychology of precariousness, I would like to remember a certain scene from the Australian TV series »Satisfaction«. Satisfaction is about a luxurious brothel in Melbourne. The place is called »232«, and it is an upmarket city brothel. Usually, the place is portrayed as a »Temporary Autonomous Zone«. Clients are like patients who appreciate the girls for solving their most touching problems. Girls are portrayed as the ones who are in control. They decide what they would reject or accept and only them. All the horrible facts of real life are left outside this utopian place, where fantasies are used to heal the wounds both clients and girls have because of real life outside the brothel. Yet, in one episode, we encounter a situation where trust in the brothel is broken. One of the girls, Tippi, is having a session with a regular client who likes a bit harsh sex. Tippi offers to use a safeword and the client accepts. The safeword they agree upon is »cherry«. That means he will stop whatever he is doing if Tippi says »cherry«. But the worst scenario happens, he does not stop although he hears the safeword. That is the first shock for Tippi. Then she presses the alarm button that is supposed to save her immediately. All the girls rely on that alarm system. Nevertheless, the alarm system is also broken and although Tippi presses it several times, it does not work. Tippi, feeling all the disappointment and fear and mistrust and loneliness, decides to save herself and kicks the client in the balls as hard as she can!

This is where we see precariousness naked: a situation where you have to kick the man in the balls yourself although you believe that you are in a luxurious brothel which is totally safe with its alarm system and elite clients. You can't trust any agreement (safewords etc) or any external authority (union, alarm etc.) anymore. You enter a fluid mental space where everything can happen, even that which poses as the opposite.

Fluidity and flexibility are obvious references to form. Fluidity and flexibility, define forms of relationships, forms of relations. But no form is itself emancipatory. I would argue that precariousness is a sadomasochistic experience without trust and it is not a traditional rape either. Values are all simulated.

There are two main points I am trying to make. a) In the precarious age, where all values are shifting, it is not easy to defend the exploited against the exploiter, it is not easy to defend the victim and struggle against the evil. Power relations are not just power relations but they are also power plays. At least they behave like one. Which makes it all the more difficult to take sides. And to construct a critical stance in this context, we need to find a way to embrace the precarious existence, instead of defining it from outside. And b) precariousness and post–Fordism shows us that forms like fluidity or flexibility are not themselves emancipatory. They can be used as political tools to cancel hierarchy; but they can also be used by the hierarchical system to impose authority. Thus, our understanding about forms becomes more vital than our form preferences.

[b]Anarchist Ethics[/b]

This is where anarchism fits in. Anarchism is a political ideology and movement which mainly emphasises form. The anarchist concern in politics is always about form: how shall we organise? What kind of form should our relationships take while we are trying to change the world? This is why prefigurative politics are vital: the form we take today shall reflect the form we want. Yet, anarchism does not imply a certain, predetermined form of relationships as the best form they can ever take. Instead, what we get from anarchism is ›an understanding about form‹. It is an understanding of an »ethical compass«. Anarchism tells us to be totally careful about forms according to an ethical compass which is based on anarchist ethics.

Ethics has been and still is central to anarchist politics. In fact it is the defining feature of anarchism, as Jesse Cohn reminds us, the historical anarchist movement »presented a socialist program for political transformation distinguished from reformist and Marxist varieties of socialism by its primary commitment to ethics, expressed as 1. a moral opposition to ›all‹ forms of domination and hierarchy [...] and 2. a special concern with the coherence of means and ends.« (Cohn 2006: 14) Politics is not defined as the struggle for the political power which is the pyramidal centre of all political acts but instead politics is defined as a much wider concept that understands ›all‹ aspects of daily life, culture, arts, struggles, etc as political, and resists reducing anarchism to anti–statism. The supposed domination of theory over practice is rejected, leaving its place to an understanding of anarchism which is identified by theory and practice at the same time, without the domination of any one of them over the other.

So, I will give several examples from anarchist history and offer a short trip through anarchism where we can glimpse anarchistic understandings of form that can, in an indirect way, help us to imagine how to deal with new problems we are having with forms of relationships and forms of struggle in a precarious age.

For example, in his »On the Question of Form,« Kandinsky wrote: »Anarchy consists rather of certain systematicity and order that are not created by virtue of an external and ultimately unreliable force, but rather one's feeling for what is good.« (Lindsay & Vergo 1982, p. 242) Kandinsky's understanding chimes with what Cindy Milstein would call the ›ethical compass‹ of anarchism. (Milstein 2010) And it is meaningful that he discussed this anarchist personal ethics while he was writing on the question of ›form‹. In a »Letter to Schonberg in August 1912«, Kandinsky specifically noted that his notion of anarchy was also »found in his experimental theatre piece ›The Yellow Sound‹«. And he ensured that although this ›anarchy’ in ›The Yellow Sound‹ has been taken as ‘lawlessness’ by some, in fact it should be understood as an order (in art, construction) which is, however, rooted in another sphere, in ›inner necessity‹«. (Jelavich 1985, p. 232.)

Landauer’s valorization of the process, ›the ongoing process of individuation‹ is a key anarchist principle. (Cohn 2010, p. 424). It is in ›making social psychology that we make the revolution‹ says Landauer (Cohn 2010, p. 425). This is another of Landauer's ideas which explains the anarchist emphasis on the process rather than the end. And it indicates the significance which anarchists attach to ›building‹ and place on ›making‹: that is, on constructing social forms. Commenting on radical queer networks and queer events, Brown also suggests that »queer (temporary) spaces stem from a desire to experiment with new forms of freedom.« (Brown 2007, p. 2697). The important point is that he sees these places as anarchistic ‘›experiments with form‹. For anarchists like Milstein, this interest in form runs counter to the reduction of anarchism to anti–statism. Defending process and form, Milstein writes:

»Anarchism’s generalized critique of hierarchy and domination, even more than its anticapitalism and antistatism, sets it apart from any other political philosophy. It asserts that every instance of vertical and/or centralized power over others should be reconstituted to enact horizontal and/or decentralized power together.« (Milstein 2010, pp. 39–40)

Milstein’s assertion reminds us that anti–statism is not the main axis in anarchism and that decentralization and horizontalism are decisive. Anti–hierarchy and anti–domination are the vital principles for anarchists and they open up different, multiple and fluid sites for resistance and engagement. Milstein adds: »the work of anarchism takes place everywhere, every day, from within the body politics to the body itself.« (Milstein 2010, p. 41)

What defines anarchism is not so much a position against state but a politicized ethics towards life. Thus, anarchist politics is never pragmatic but always prefigurative. Anarchism »keeps this vigilant voice constantly at its center, as its core mission« asking »what is right?« »What is the right thing to do?« (Milstein 2010: 47)

On this account anarchism is ›the‹ political philosophy that defines all these areas excluded from the canon as parts of the political and which distinguishes itself from other political philosophies by insisting on this.

[b]Creative Anarchy[/b]

The post–war avant–garde composer John Cage (1912–1992) also expressed his anarchism in his art works, especially through their form. Cage »favoured a structure that is nonfocused, nonhierarchic and nonlinear.« (Kostelanetz 1993, p. 47) His radical works were »expressed in decisions not of content but of form.« (Kostelanetz 1993, p. 47) In his works, there was no need for a conductor for example, as he was writing music for an ensemble of equals, and »the principle of equality extended to the materials of his art as well«. (Kostelanetz 1993, p. 47) Lewis Call observes that Ursula Le Guin's novels, which popularize anarchist ideas are, like John Cage's music also »relentlessly experimental« in their form. For example »The Left Hand of Darkness«, her 1969 novel »has no narrative center«. Similarly, Eric Keenaghan observes, in twentieth–century poet Robert Duncan's (1919–1988) anarchistic philosophy, »poetry is not a revolutionary's tool; rather, it is a creative means of striving toward an alternative vision of life, one rivaling the state's idea of what life ought to be.« (Keenaghan 2008, p. 635)

Commenting on John Henry Mackay's ›novel‹ »The Anarchists«, Peter Lamborn Wilson (widely known as Hakim Bey) reminds us that Mackay »never intended his anarchist narratives to be read as novels, but rather as ›bastard‹ or translational hybrid ›forms‹ made of narrative and polemic.« (Wilson 1999, p. xvii emphasis added.) Kandinsky, like Mallarmé, believed in the effectiveness of art work as a ›weapon‹: he »found the concept of dissonance in music as liberating as the student disturbances at the university.« (Long 1987, p. 43)

Peter J. Bellis, in his »Writing Revolution«, traces a similar anti–hierarchical form in Walt Whitman's poetry, especially in the first, 1855 edition of Whitman’s »Leaves of Grass«. Belis notes that Whitman attacks »the kind of poetic privilege that would distinguish between aesthetic and the factual or historical«, he »abandons symbolic or metaphoric representation, in which one thing stands for another, in favour of anti–hierarchical, inclusive catalogues punctuated only by ellipses and commas.« (Bellis 2003, p. 72) For Bellis, the »initial radicalism of ›Leaves of Grass‹ thus goes far beyond the level of literary form; its ultimate goal is the visionary reconstruction of national, gender, and individual identity [...]« (Bellis 2003, p. 73) »In political terms,« Bellis equates »the consequence of Whitman's claims« to »direct democracy.« (Bellis 2003, p. 79) Whitman has always been an important figure both for anarchists and queer activists. He was a »celebrated figure among many anarchists who saw a lyrical validation of their own beliefs in his work.« (Kissack 2008, p. 69) As Leonard Abbott suggests, »homosexuals all over the world have looked toward Whitman as toward a leader.« (Kissack 2008, p. 70) Edward Carpenter can be named as one of these homosexuals. Carpenter had a certain influence on European anarchism and queer activism (and also on John Mackay). Whitman was so influential for Emma Goldman that, in 1905, she decided to name her new anarchist journal: »The Open Road«. »The title was inspired by the work of Walt Whitman.« (Kissack 2008, p. 69) Just because the »name ›The Open Road‹ was already taken,« Goldman switched to the now famous title »Mother Earth«. (Kissack 2008, p. 69) »In an early article in Mother Earth titled ›On the Road‹1 Emma Goldman urged her readers to follow Whitman on the »open road, strong limbed, careless, child–like, full of ›joy‹ of life, carrying the message of liberty, the gladness of human comradeship.« (Kissack 2008, p. 69, emphasis added) In his »Free Comrades, Anarchism and Sexuality In the United States«, Terence Kissack devotes a whole chapter to ›Walt Whitman and anarchism‹. (Kissack 2008, Chapter 3 pp. 69–95.) Whitman's ›open road‹ was suggestive of ›sexual freedom‹ to his anarchist readers. »Anarchist discussions of Whitman and his work in the nineteenth century reflected the prevailing erotic interpretations of Whitman's writing. The discussions and debates that did occur in the movement largely made reference to illicit relations between men and women that figured in the work.« (Kissack 2008, pp. 69, 72). Perhaps not surprisingly, Gustav Landauer was one of the early German translators of Whitman’s poetry and he admired enormously »Leaves of Grass«. (Maurer 1971, pp. 97–98).

Responding to an 1893 poll of writers and artists in a French journal about their political views, Oscar Wilde said »I consider myself an artist and an anarchist.« On another occasion he affirmed: »I am something of an anarchist.« (Kissack 2008, pp. 48). Anarchist writers in France, Octave Mirbeau, Paul Adam and also painter Toulouse–Lautrec directly showed their solidarity with Wilde during his trial by writing articles and designing posters. »Anarchists were among the few public defenders of Wilde during his trial and its aftermath.« (Kissack 2008, p. 54). Wilde also drew on anarchist ideas and texts in the construction of his work. (Kissack 2008, p. 48). Queer activism, bending the borders of ›the normal‹ in sexual life, experimenting with new and free forms of sexual relations: artistic avant–garde experimenting with new and free forms of art works; and the political radicalism of anarchism, experimenting with new forms of social, economic and political relations have always been linked with each other. All these dynamics were intermingled at the time of Oscar Wilde's trials and they are still in today’s movement.

Neal Ritchie, an active participant of queer anarchist activists in Asheville, North Carolina, says »[...] the conception of queer as a politically subversive project [...] to a large extent reflects the growing popularity of anarchist politics [...]« (Ritchie 2008, p. 261). Ritchie also points out the cross–pollutional nature of anarcho–queer relations: »Much of contemporary queer youth's tactics, organizational structures, and overall goals have been heavily influenced by anarchism. Simultaneously, large anticapitalist demonstrations from Berlin to Quebec to Buenos Aires have borrowed from the aesthetics and carnivalesque qualities of many queer youth cultures [...]«2 (Ritchie 2008, pp. 261–262). Indicating the qualities of the concept of queer, Ritchie says »there is a wonderful flexibility and anarchic character to the word 'queer'.« (Ritchie 2008, p. 270). We can remember here that while discussing these anticapitalist demonstrations, Brian Holmes calls their aesthetic a ›precarious protest aesthetic‹. (Holmes 2009, p. 111).

Queer is widely used as an umbrella term »for all those who are ›othered‹ by normative heterosexuality [...] Queer celebrates gender and sexual fluidity and consciously blurs binaries. It is more of a relational process than a simple identity category« (Brown 2007, p. 2685). Terence Kissack argues that »historians of American anarchism have not fully appreciated the importance of the anarchists’ politics of homosexuality.« (Kissack 2008, p. 7) The London group Queeruption »has no executive or officeholders; decisions are reached by consensus whenever possible [...]« (Brown 2007, p. 2687) Although mostly concentrated in Western Europe and Northern America, the radical queer network is international, with links to »radical queer groups in Argentina, Israel/Palestine, Serbia and Turkey«. (Brown 2007, p. 2689). Another example of ›cross–pollination‹ between anarchism and the queer movement:

»[...] the activism of the Queeruption network is not limited to sexual and gender politics. It offers an anticapitalist perspective to queer activism and a queer edge to the anticapitalist movement. Activists from the network have participated in many of the larger mobilisations and convergences of the global justice movement and the grassroots anticapitalist networks within it – sometimes working explicitly as a queer bloc, at others in affinity with other groups.« (Brown 2007, p. 2690).

Eric Keenaghan, while working on the queer anarchism of the poet Robert Duncan, notes that Duncan was »one of the innovators of open–form poetics.« (Keenaghan 2008, p. 634). This ›open–form poetics‹ is reminiscent of Uri Gordon's view on anarchism. Gordon claimed that in the ideological core of contemporary anarchism lies an »open–ended, experimental approach to revolutionary visions and strategies.« (Gordon 2007, p. 29). Pointing to the same feature of anarchism, Cindy Milstein adds: »From the start, anarchism was an open political philosophy, always transforming itself in theory and practice. This, too, might be seen as a part of its very definition. Anarchism has to remain dynamic if it truly aims to uncover new forms of domination and replace them with new forms of freedom[...]« (Milstein 2010, p. 16). Thus she gives us another point which shows the importance of ›forms‹ in anarchist history. So anarchism is not a continuous form, an everlasting form of organization, but a coherent understanding about the form!

Lewis Call praises Le Guin in similar terms for developing »new forms of anarchist thinking.« (Call 2007, p. 88). Call argues Le Guin creates »new forms of anarchism that are entirely relevant to life in the postmodern condition,« and her fiction has »an ability to call into question the forms of scientific, technical and instrumental reason that have come to dominate the modern West.« (Call 2007, p. 89).

[b]Form and Ideology[/b]

Anarchist insistence on form is an important part of my argument. The form of the movement is its ideology, and its form is a constant renovation according to an ethical compass and constant experimentation. This is not formlessness (remembering Landauer’s saying, »we need forms, not formlessness«) but a continuous changing of form, within which anarchism manages to retain an allegiance to the ›anarchist principle‹, its ethical compass. That makes anarchism the political compass in a precarious age. Anarchist artists worked on form tirelessly and these experiments in form were always directed towards a more libertarian alternative, in a dialogue with anarchist experiments for more libertarian forms for life. Patricia Leighten, working on the anarchist politics of modernism in art, stated that the most notable fact of

»modernism is its ›revolutionary‹ style: abrupt transitions, anti–narrative structure, surprising juxtapositions. Such techniques depart from traditional ›naturalistic‹ modes of discourse and communicate their all–important innovative relation to form. In pre–World War I France, many modernists – including Pablo Picasso, Frantisek Kupka, Maurice Vlaminck, and Kees van Dongen – thought anarchist politics to be inherent in the idea of an artistic avant–garde and created new formal languages expressive of their desire to effect revolutionary changes in art and society.« (Leighten 1995, p. 17).

Thus »a ›revolutionary esthetics‹ – a politics of form – played a crucial role in the development of modern art in prewar France, but its significance was first suppressed and then forgotten.« (Leighten 1995, p. 17).Anarchism itself was and still is a ›politics of form‹. In a parallel way, revolutionary aesthetics played a crucial role in the development of modern anarchism. This role has also been forgotten in the anarchist canon! The cultural amnesia or political amnesia about the role that the arts, women, queer and culture itself have played in the history and configuration of anarchism, is rooted in the modern rationale – the perspective that tends to reduce anarchism to ‘›anti–statism‹.

Jean Grave’s success in mobilizing artistic creativity in his anarchist magazines was a result of the encouragement he gave to artists to be free, to experiment, rather than requiring them to be tools for the anarchist cause.

[b]Free Love Gets Stabbed![/b]

The well–known Japanese anarchist and writer Osugi Sagae’s anarchism »was not concerned exclusively with society and its organizational reform: it focused equally on the perfection of the individual by the individual’s own action; by that means society too would be perfected.« (Stanley 1982, p. xi). For Osugi, like Goldman, the personal was political already. His relations with Emma Goldman’s politics would probably have been more extensive, had he known her better. The only difference between the two is that while Goldman was practicing her theories of free love relatively ›freely‹, Osugi, a victim of jealousy, was stabbed by one of the three women he was supposed to be in a ›free love‹ relationship with!

[b]The Anarchist Strategy Of Inversion[/b]

As Whimster argues, »avant–gardes [...] were pitching for their own redefinition of modernity and to this end were creating and deploying innovative artefacts: new forms in art, literature, life–style and ›politics‹, producing entirely new aesthetic and ethical sensibilities. The political has, as always, to be seen as the struggle for the possible.« (Whimster 1999, p. 5). By ›avant–gardes‹, Whimster meant both anarchists and avant–gardes in visual arts and literature. In Klaus Lichtblau's words, modernisms could be »taken as revolutions in the basis of thought and the forms through which the world was recognised.« (Whimster 1999, p. 4). For Otto Gross, »if a desire was sexual then it was perverse to deny it.« (Whimster 1999, p. 16). This is just what Lawrence thought about Tolstoy: a pervert.

As if to echo anarchist activists who think that a ›non–gendered‹ relationship would fit anarchist ideals, in Le Guin's »Left Hand of Darkness«, we encounter the inhabitants of Gethen who are »human but they do not have the binary gender system that characterizes most human societies. Gethenians spend most of their lives in an androgynous state, neither male nor female.« (Call 2007, p. 92). In harmony with queer anarchist politics of today, »On Gethen, gender identity is [...] provisional, temporary and arbitrary. For Gethenians [...] gender is no absolute category.« (Call 2007, p. 92).

Just as Lawrence accused Tolstoy of being ›perverse‹ »to make her critique of real world gender categories as explicit as possible, Le Guin introduces us to the Gethenian concept of perversion.« (Call 2007, p. 94). Using what Leighten would call an anarchist strategy of inversion, Le Guin (and actually Lawrence) categorize what we call normal as ›perverse.‹

Lewis Call underlines the successful service of anarchist propaganda accomplished by Ursula K. Le Guin's popular science fiction and fantasy novels: »By describing anarchist ideas in a way that is simultaneously faithful to the anarchist tradition and accessible to contemporary audiences, Le Guin performs a very valuable service. [...] She introduces the anarchist vision to an audience of science fiction readers who might never pick up a volume of Kropotkin.«3 Considering her »frequent critiques of state power, coupled with her rejection of capitalism and her obvious fascination with alternative systems of political economy« Lewis Call thinks it is »sufficient to place her within the anarchist tradition.« (Call 2007, p. 87). In a number of examples we see how various contexts convincingly suggest the inclusion of cultural figures, writers, women and queer anarchists and artists within the anarchist tradition. Some suggest the inclusion of Mirbeau here, the Marquis de Sade there, or Ursula Le Guin somewhere else.

[b]Behaving Differently[/b]

»The State is a condition, a certain relationship between human beings, a mode of behaviour; we destroy it by contracting other relationships, by behaving differently toward one another [...] We are the State and we shall continue to be the State until we have created the institutions that form a real community.« (Gustav Landauer, 1910) This famous saying of Landauer has been quoted widely by anarchists, because it perfectly captures the importance of the prefigurative principle. The »[c]onstruction of prefigurative social institutions as functioning alternatives to extant systems of domination« (Horrox 2010, p. 189). means ›relating differently‹, as Jamie Heckert would say; it is not formlessness but a search for new forms. »Under Landauer’s editorship ›Der Sozialist‹ came to be widely viewed as one of the best anarchist newspapers on the continent.« (Horrox 2010, p. 190). For Landauer, anarchism was »a basic mood which may be found in every man who thinks seriously about the world and the spirit [...] The impulse in man to be reborn, to be renewed and to refashion his essence, and then to shape his surroundings and the world, to the extent that it can be controlled.« (Horrox 2010, p. 193.)

Accordingly, in anarchism knowledge is shared and distributed in a rhizomatic fashion. Anarchist texts are shared in the form of »zines, newsletters, blog posts, links on social networking sites, and a few major websites that serve as electronic hubs for the distribution of anarchist information.« (Portwood–Stacer 2010, p. 486.) There is no ›party organ‹ or a central publication for the militants to follow, but there are numerous endless linkages of small publications without any central role, being linked to each other worldwide. »Anarchist songs, newspapers, poems, posters, speech and celebrations formed a coherent culture of anarchism.« (Sonn 1989, p. 30.)

As another demonstration of the importance of form for anarchists (but not formlessness), anarchist conferences restrict behaviours. For example the policy of Auckland Anarchist Conference was as follows:

»People attending this conference are asked to be aware of their language and behavior, and to think about whether it might be offensive to others. This is no space for violence, for touching people without their consent, for being intolerant of someone’s beliefs or lack thereof, for being creepy, sleazy, racist, ageist, sexist, hetero–sexist, trans–phobic, able–bodiest, classist, sizist or any other behavior or language that may perpetuate oppression.« (Nicholas 2009, p. 11.)

Returning to the precarious condition we are living in, I would say that the untrustful environment of the precarious existence shows us perfectly how the forms of relationships are not themselves oppressive or emancipatory. It is rather the understanding about form, that matters.

[b]Bibliography[/b]

Bellis, P. J, »Writing Revolution, Aesthetics and Politics in Hawthorne, Whitman, and Thoreau«, The University of Georgia Press. Athens and London 2003.

Berry, D, ›Workers of the World, Embrace!‹, Daniel Guerin, the Labour Movement and Homosexuality', »Left History«, vol. 9, no.2, 2004, pp. 11–43.

Brown, G, ›Mutinous eruptions: autonomous spaces of radical queer activism‹, »Environment and Planning A«, vol. 39, no. 11, 2007, pp. 2685–2698.

Call, L, ›Postmodern Anarchism in the Novels of Ursula K. Le Guin‹, »SubStance« vol. 36 no.2, 2007, pp. 87–105.

Cohn, J, »Anarchism and the Crisis of Representation: Hermeneutics, Aesthetics, Politics«, Susquehanna University Press, Selingsgrove, 2006.

Cohn, J, ›Sex and the Anarchist Unconscious: A Brief History‹, »Sexualities«, vol. 13, no. 4, 2010, pp. 413–431.

Gordon, U, ›Anarchism Reloaded‹, »Journal of Political Ideologies«, vol. 12, no.1, 2007, pp. 29 –48.

Holmes, B, ›Marcelo Exposito's Entre Suenos, Toward a New Body‹, »Open«, no:17, 2009 pp. 100–115.

Horrox, J, ›Reinventing Resistance: Constructive Activism in Gustav Landauer’s Social Philosophy‹, in Jun, N. and Wahl, S. »New Perspectives on Anarchism«, Lexington Books. Lanham, Boulder, New York, Toronto, Plymouth –UK 2010.

Jelavich, P, »Munich and Theatrical Modernism: Politics, Playwriting, and Performance, 1890–1914«, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London 1985.

Keenaghan, E, '› ‹Life, War, and Love: The Queer Anarchism of Robert Duncan's Poetic Action during the Vietnam War', » «Contemporary Literature, vol. 49, no. 4. 2008 pp. 634–659.

Kissack, T. »Free Comrades: Anarchism and Homosexuality in the United States 1895–1917«, AK Press.Edinburgh 2008.

Kostelanetz, R, ›The Anarchist Art of John Cage (1912––1992)‹, »Anarchist Studies«, vol. 1, no. 1. 1993, pp. 47–50.

Landauer, William G. ›Weak Statesmen, Weaker People,‹ Der Sozialist. Excerpted in »Anarchism: A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas — Volume One: From Anarchy to Anarchism (300CE-1939)«, ed. Robert Graham, Black Rose Books. Montreal 1910/2005.

Leighten, P, ›Reveil anarchiste: Salon Painting, Political Stire, Modernist Art‹, »Modernism/Modernity«, vol. 2, no. 2. 1995, pp. 17–47.

Lindsay, K. C. & Vergo, P. (ed. by) »Kandinsky, Complete Writings on Art, Volume I (1901–1921)«, Faber and Faber. London1982.

Long, R–C. W. ›Occultism, Anarchism and Abstraction: Kandinsky's Art of the Future‹, »Art Journal«, vol. 46, no. 1. 1987 pp. 38–45.

Maurer, C. B, »Call to Revolution, The Mystical Anarchism of Gustav Landauer«, Wayne State University Press. Detroit 1971.

Milstein, C, »Anarchism and Its Aspirations«, AK Press/The Institute for Anarchist Studies. Oakland, Edinburgh and Washington 2010.

Nicholas, L, ›A Radical Queer Utopian Future: A Reciprocal Relation Beyond Sexual Difference‹, »Thirdspace«, vol. 8, no. 2. 2009.

Oudenampsen, M, '›Precariousness in the Cleaning Business‹, »Open«, no: 17, 2009, pp. 118–131.

Portwood–Stacer, L, ›Constructing Anarchist Sexuality: Queer Identity, Culture, and Politics in the Anarchist Movement‹, »Sexuality«, vol. 13, no. 4. 2010, pp. 479–493.

Ritchie, N, ›Principles of Engagement: The Anarchist Influence on Queer Youth Cultures‹, in Driver, S. (ed. by) 2008, »Queer Youth Cultures«, State University of New York Press. New York 2008.

Seijdel, J, ›A Precarious Existence‹, »Open«, no: 17. 2009, pp. 4–5.

Sonn, R. D, »Anarchism and Cultural Politics in Fin De Siecle France«, University of Nebraska Press. Lincoln and London 1989.

Stanley, T. A, »Osugi Sakae, Anarchist in Taisho Japan: The Creativity of the Ego«, Council on East Asian Studies, Harvard University. Cambridge, Mass. 1982.

Whimster, S, »Max Weber and the Culture of Anarchy«, Palgrave Macmillan. London 1999.

1 »On the Road« would later be the title of one of most read Beat Generation novels written by Jack Kerouac. The Beat Generation was inspired both by Whitman and anarchism.

2 Today, radical queer networks are political spaces where people can get radicalized and queer at the same time relatively easily. While the times were harsh for queers, Guérin put a lot of effort into the struggle for his own queer politics, and he describes his formation in the following terms: »I found myself to be at once a homosexual and a revolutionary [...]« (Berry 2004, p. 13).

3 This is even true for me: I myself was dragged to anarchism through Le Guin and love; when at the age of 16 I fell in love with a girl who became an anarchist after she read a Turkish edition of The Dispossessed and who was talking of Anarres all the time!