Issue 4/2013 - Kunst der Verschuldung

Art and debt

The relationship between current practices and the ongoing crisis

The debt crisis that broke out five years ago did not merely transform millions of lives, but also shook economists’ claims to hold a prerogative in interpreting economics. Art has approached this nexus of topics with great caution so far, given the rather diffuse mood of uncertainty that has prevailed since the crisis began. This however is not due to indebtedness or empty coffers. It is much more that the art market has profited from the crisis-typical “flight” of wealth to (supposedly) solid assets, in the process entrenching the symbiosis it had constructed with the financial capitalism’s elites during the preceding boom years.

The record figures obtained for artworks are one manifestation of the increasing role of economic and financial considerations in art. This development has been driven by the strong growth and increasingly international scope of some areas of the fine arts, and in particular by the rapid spread of art fairs and biennials1, a phenomenon that cuts across the continents. With the auction houses’ incursion into the contemporary art scene since the late 1990s, and an emerging “celebrity culture”2 , art’s economisation has been further reinforced.3

Whilst initially the art market managed to escape most serious consequences of the crisis, the latter crisis became an unavoidable point of reference and a source of raw material for art production. This can be felt too in shift in the discursive frame of reference; the spectrum of buzzwords generated by those who shape opinions in the art world now increasingly turn the limelight on topics related to the economy.

There is not one single major art show that has not included the crisis in the subjects it tackles. Works that fall into this category can be sub-divided in terms of three distinct ways of addressing the topic.

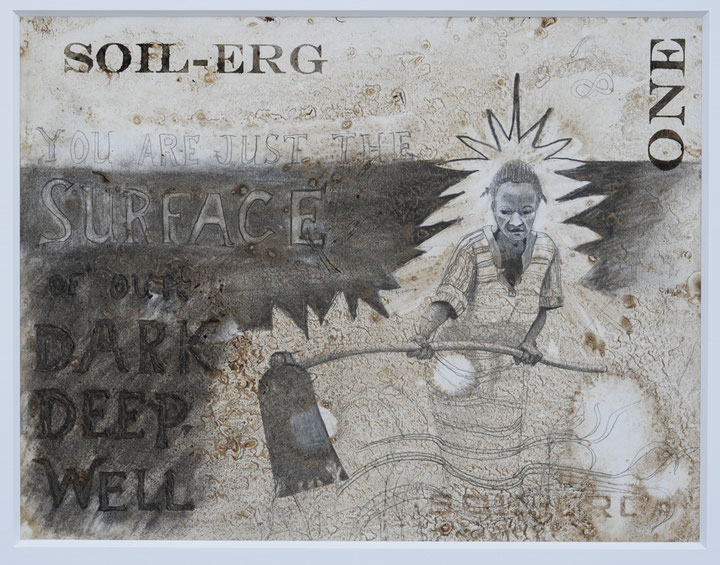

The first approach seeks to depict crisis-related phenomena and to engage in or import crisis analysis. In the Greek pavilion at the latest Venice Biennale, Stefanos Tsivopoulos’ three-part video installation History Zero examines the current political and economic situation in debt-ridden Greece through the prism of an African migrant who collects scrap metal, an ageing female art collector who makes origami flowers out of Euro notes and a dapper artist with his tablet on a poverty tourism trip in search of motifs and inspiration. An exhibition series on the financial and economic crisis, curated by Gregory Sholette and Oliver Ressler, and citing Slavoj Žižek in its title It’s the Political Economy, Stupid, was shown in Vienna, New York, Thessaloniki and Pori and brought together artists as different as Dread Scott, Alicia Herrero and Melanie Gilligan. In her video works Crisis in the Credit System and Popular Unrest, Gilligan explores contemporary finance-dominated capitalism in a poetic episodic format that draws on TV series.4 Last but not least, the 2013 steirische herbst 2013 is attracting visitors with an exhibition entitled Liquid Assets in which artists address the opacity of financial systems, and promises to enlighten us about money, credit and banks in a crash course on economic theory for dummies by Amund Sjølie Sveen.

A second approach adopted by crisis-related art involves presenting proposals for alternative economies. At the last documenta, for example, e-Flux editors Julieta Aranda and Anton Vidokle presented the “Time/Bank” project, which proposes using working time rather than money as a unit of exchange. Claire Pentecost also showed her work at documenta, an installation setting up a model rooted in arable land as an alternative currency, in direct contrast to the prevailing monetary and financial systems. Finally, at this year’s Venice Biennale, the rotunda at the entrance to the Greek pavilion was adorned with a heterogeneous panorama of 32 alternative currency, barter and economic models, ranging from the hacker currency Bitcoin to the most hyped instrument of development aid in the 2000s, micro-credits.

The genre of artistic interventions forms the third approach. Last year the Berlin Biennale brought activist critique of the financial system into the White Cube in the form of an Occupy camp. The initiative “Strike Debt”5 by action artist Thomas Gokey (in $49,983 he created an installation out of dollar notes he had put through the shredder) and Canadian/American filmmaker Astra Taylor (best known for her documentary about Žižek) used donations to buy – inspired by Occupy Wall Street –impoverished Americans’ debt to cancel their debt burden.

From an analytical perspective most of these approaches clash with the most apparent phenomenon of the crisis and the central capitalist fetish: money and its relationship to debt. Tsivopoulos’ work is a rare exception, developing a more self-critical reflection on art’s role. In most other cases the predominant perspective is rooted essentially in importing, illustrating or accompanying analyses and critiques of the crisis that are in any event in circulation and adopting their debtor-centred perspective.

What sources do artists draw on here? A search of art journals, exhibition texts, conferences and catalogues for references to the crisis will first and foremost turn up two names: David Graeber and Maurizio Lazzarato. The anarchist anthropologist Graeber was briefly a star of both social movements and bourgeois culture supplements thanks to his book Debt. The first 5000 years6. Since the mid-1990s the philosopher Lazzarato has been consulted on a regular basis, along with other Post-operaists such as Antonio Negri and Paolo Virno, when discussions on immaterial work and mass intellectuality in the field of art have been on the agenda.7

Graeber’s book Debt. The First 5000 Years, which sometimes seems to have been produced at top speed in response to the surprising pressure of topical events after the outbreak of the crisis, sets the question within a history of money and credit that has unfolded for millennia. From this perspective he casts doubt on many of the myths in circulation about how money came into being in response to a need to simplify barter, which has purportedly accompanied humanity since the dawn of time. However, the alternative reading that Graeber proposes of a continuity between credit practices in Antiquity and in the contemporary world, t and his attempt to construct a cyclical theory of the alternating dominance of hard cash and money in the form of loans provide only limited assistance when it comes to understanding the most recent crisis. He would simply see this as one more in a sequence of countless episodes in which pressure for debts to be forgiven has welled up in interactions between creditors and debtors. In Graeber’s view, all that has changed in capitalism is the form of the debt (namely precisely detailed accounting rather than informal approaches), but not its function and systemic significance. Graeber relies on a cooperative attitude in interactions between people as the crucial starting point in bringing about change: the possible consequences of that kind of attitude range in his view from debt cancellation to the establishment of cooperative modes of production. It is rare to find such close links to practical everyday behaviour in the world of grand theories and this, along with perfect timing, for his book was published at the start of the Occupy Wall Street protests, explains much of Graeber’s success.

Although it adopts an equally sweeping perspective, Maurizio Lazzarato’s The Making of the Indebted Man8 engages in a more precise analysis of the context. In his view debts are also a means of subjectivation, whereby conformist willingness to work is fostered by a moral code that equates debt in the economic sense with debt in the moral sense of the term, and the ensuing conclusion that debts must always be paid, a counsel that Benjamin Franklin in his day already doled out to the “young salesman” as well as to “people who want to get rich” – in Max Weber’s analysis, one of the ideal-typical rules embodying the capitalist spirit. Lazzarato explains that nowadays capitalism is rooted in this mechanism to a greater degree than ever before. The neo-liberal model of the “entrepreneur of the self” has been replaced in the last decade by the social figure of the indebted individual.

Lazzarato is an appealing source of slogans for art circles above all because he describes the “debtor” as a subject type with more than a purely economic function. This fits right in with the great importance ascribed to subjective approaches in the art field. For in that context promises of the kind of “radical chic” that resonate in activist practices are still very much in demand. In this respect a certain “militant capital”9 claimed by both the former Autonomia Operaia activist and the anarcho-anthropologist most certainly fosters their reception in art circles.

Blanked-out assumptions

But does successful reception within art circles also reflect an innovative academic contribution to elucidating the significance of credit in contemporary capitalism? Graeber and Lazzarato are by no manner of means the first to have tackled the topic. The significance of debt is however a controversial issue in economics. Conservatives and right-wing liberals tend to viewed accumulating debt as reprehensible and as indicative of a lack of discipline concerning saving and work. Liberal thinker Ralf Dahrendorf coined the term “pump capitalism” to describe this in the context of the crisis. Many commentaries on the crisis-ridden southern countries by German politicians echo this attitude. In Keynesianism, in contrast, debt is essentially viewed as an important instrument that enables investment and survival of temporary slack periods. The question in economic policy in actual practice is therefore rather what level of debt is problematic, and which circumstances make it so.

In particular, the issue is whether these circumstances have undergone a historical change and, if so, how this could be characterised. Over the last decades debt has actually begun to assume a different macro-economic significance, and can now be referred to as a system-stabilising factor. For a very long time firms all over the world put the brakes on their workforce’s wages. But with a modest income you can only make modest purchases. Companies however, need customers with purchasing power in order to sell their goods. The gap is filled by loans granted to states and private households (above all in the USA and on the periphery of the EU) by financial institutions on a global expansion course. Such loans made it possible, temporarily, to turn modest-income regions and segments of the population into profitable sales markets. However, if debt is not used for investment in value-creation, thus opening up new sources of income, but instead is needed primarily to compensate for shortfalls in consumer budgets, repayment problems begin to arise after a certain level of debt is reached. That threshold seemed to have been crossed in 2007/08. The consequences were – and still are – private individuals going bankrupt, investors fleeing sovereign bond markets, adjustment programmes that include ending state benefits and the ensuing domino effects, such as company closures and unemployment have been. Meanwhile state bail-out packages for the financial sector stabilise private-sector assets. And therefore also stabilise the wealth of the financial managers and other prosperous individuals who finance the art market and who, as a reaction to the shock of the crisis, have in some cases once again turned their back on nebulous securities and restructured their investments to focus on seemingly more solid artworks.

Marxist writers such as Costas Lapavitsas10 and Christian Marazzi11 emphasise that the populist good/evil dichotomy with reference to productive capital and financial capital, which is also implicit in some of the artworks cited, is erroneous. If only loans and financial bubbles make it possible to maintain the current level of accumulation within the existing power structure, then the credit sector, rather than just being an annoying appendage, plays a key role for the entire economy. Simply “putting banks in their place” – as Occupy Wall Street activists sometimes demand – or fantasising about a “different kind of money” is thus not a solution unless an alternative means of producing prosperity is found or unless economic needs can be provided for by some other means.

The fact that artists also take analytical problems on board when they import theories is not a unique characteristic of art, which means this is also not the greatest problem. Since reception of discourses on legitimation has shifted from the more philosophical emphases of the “French Theory”12 that once predominated towards a greater emphasis on economic questions, one might have expected that the old antimony between art and economy would be addressed too. However, the economic realm and thinking about it are generally addressed as external fields. The writer or artist’s own position is understood, implicitly or explicitly, as sympathising with the debtor’s position, but reflection generally stops there.

One might expect that works with a self-image of being part of a conceptualist tradition would include the conditions of artistic production and reception among their themes. There is however scarcely any sign of that kind of approach in work grappling with the most recent crisis. The structural anti-economistic habitus of creative subjects, which – to cite Bourdieu – is characterised by participation in the constitutive interests of belonging to the artistic field, implies accepting or blocking out many assumptions and postulates, such as a fundamental economic disinterest, which, as an unquestionable pre-condition of the discussion wishes to be protectedfrom discussion.

In this context Andrea Fraser has pointed out that artists tend to be part of the problem than part of the solution. In her essay L’1%, c’est moi she demonstrated, using empirical material on the increased income of powerful elites, how the financial bubble had helped the art market to boom again. In her commentary on the connection between economic inequality and the development of the art market, she points out that “what was good for the art world has been disastrous for the rest of the world”. For the art market and those involved in it, that means that the more extreme inequality is with society, the more we will see “skyrocketing art prices.”13

When addressing the crisis as artistic material, the scant focus on the role of art in the contexts examined is a conflict-avoidance strategy. In financialised capitalism, art plays a considerable role by enabling elites to transform financial capital into its cultural equivalent, in the process acquiring a reputational bonus for their activities. Segments of the field of art oriented towards the market have benefited significantly from this – firstly from the financial market boom pre-crisis, and post-crisis from stabilisation of those markets at the expense of the general public. The latter will lead to savings in the public sector, which will hit the less commercial segments of art production. Inequality will therefore also be further exacerbated between artists. Rather than exhibiting Occupy tents at a Biennale, it would be more compelling to make the event itself the subject of attention instead of viewing it as a mere platform.

Translated by Helen Ferguson

1 See Oliver Marchart, Hegemonie im Kunstfeld. Die documenta-Ausstellungen dX, D11, d12 und die Politik der Biennalisierung. Cologne 2008.

2 See Isabelle Graw, Der große Preis. Kunst zwischen Markt und Celebrity Culture. Cologne 2008.

3 See Heike Munder/Ulf Wuggenig (eds.), Das Kunstfeld. Eine Studie über Akteure und Institutionen der zeitgenössischen Kunst. Zürich 2013.

4 See “Subjects of Finance. Melanie Gilligan Interviewed by Tom Holert”, in: Grey Room, No. 46, Winter 2012, p. 84–98.

5 http://strikedebt.org

6 David Graeber, Debt. The First 5000 Years. New York, 2011.

7 The “Reading list: Propadeutics to fundamental research” of the last documenta contained 18 works by Post-operaists. Judith Butler, who was cited eight times, got the most mentions, Paolo Virno came second with five, and third place was shared between Michel Serres and Franco “Bifo” Berardi along with Giorgio Agamben, Donna Haraway and Isabelle Stengers. See dOCUMENTA/Museum Fridericianum (ed.), dOCUMENTA(13) – Das Buch der Bücher, catalogue 1/3. Ostfildern 2013, p. 18–26.

8 Maurizio Lazzarato, The Making of the Indebted Man. Essay on the Neoliberal Condition. Los Angeles 2012.

9 The journal founded by Pierre Bourdieu, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, published two special editions on “militant capital”: “Le capital militant. Engagements improbables, apprentissages et techniques de lutte”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, No. 155, 2004/5; “Le capital militant (2). Crises politiques et reconversions: Mai 68”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, No. 156, 2005/1.

10 See Costas Lapavitsas, “Financialised Capitalism: Crisis and Financial Expropriation”, in: Historical Materialism, Vol. 17 (2009), S. 114–148.

11 See Christian Marazzi, Sozialismus des Kapitals. Zürich 2012 and id., Verbranntes Geld. Zürich 2011.

12 For an empirical study of theoretical influences in art, see Sophie Prinz/Ulf Wuggenig, “Charismatische Disposition und Intellektualisierung”, in: Munder/Wuggenig (eds.), Das Kunstfeld, p. 217–220.

13 Andrea Fraser, “L’1%, c’est moi”, in: Texte zur Kunst 83, September 2011, p. 123.