Issue 4/2013 - Net section

Medium as “Missive”

On Akram Zaatari’s Video Letter to a Refusing Pilot (2013)

There is an ambiguity in the lovely old-fashioned word German term “Missiv” that remains highly expressive today. On the one hand, the word refers to a written communication that is dispatched, as is also expressed in the English term “missive”–the letter that always arrives at its destination, as one of Jacques Lacan’s dictums asserts. On the other hand, and that would be, so to speak, the flipside in media theory terms, it also refers to a briefcase that can be locked: a recipient that carries all kinds of material in various media formats, which can however not be consulted directly. A letter and a lockable case, a clearly addressed message and something packed in secretly along with it–that is the crossed-over, indeed strangely paradoxical, meaning of “Missiv”.

Akram Zaatari’s video work Letter to a Refusing Pilot, produced for the Lebanese Pavilion at the 55th Venice Biennale,1 is characterised by precisely this twofold meaning. The piece does still more, actually, as the way in which it interweaves both aspects brings into play the latent tension between the (political) message and the (in a sense encyclopaedic) mediality. In addition, the approach Zaatari adopts in editing together autobiographical and historical elements generates a highly concentrated fusion and intermingling of the destination and constitution of the “Missiv”.

But first things first: Letter to a Refusing Pilot is directed, as is made explicit towards the end of the film, to the Israeli bomber pilot Hagai Tamir. He was faced with a grave decision on 6th June 1982 while on a mission to bomb a complex of buildings in Saida in southern Lebanon–the town where Akram Zaatari grew up. As a trained architect, Tamir realised from the air that the targeted complex must be either a school or a hospital, at which point he did an about-turn and dropped his deadly load over the sea. The tragic ambiguity of this individual act of refusal lay however in the fact that the Saida Public Secondary School for Boys, the building in question–where Zaatari’s father was headmaster at the time–was nonetheless destroyed: by the first available pilot who could be found to complete the mission.

The story did the rounds in Lebanon for a long time as a legend, and it was only much later that it transpired that the anecdote was historically accurate 2–another reason why Zaatari composed his letter thirty years after the devastation that was nonetheless inflicted. Just as Albert Camus attempted to subvert the frontlines of national animosity in his Letters to a German Friend , written during the Second World War, Zaatari’s “missive” undermines any notion of clearly demarcated fronts. On the one hand this applies on a personal level, namely from the perspective of a 16-year-old Lebanese school pupil (Zaatari’s younger self) vis-à-vis an adult member of the Israeli army, the two linked by the “irrational” decision to resist. On the other hand, this also holds true in terms of the time frame: even if nothing about the catastrophic event can be changed any longer, the “missive”, although it is anchored in the past, is nonetheless also directed more to contemporary or future antagonisms–seeking, on the basis of the events that unfolded, to establish the act of refusal as an attitude that could possibly offer a grain of hope in shaping the future.

That objective is precisely why it was essential to include the capacious media archaeology also inscribed in Letter to a Refusing Pilot. Zaatari actually incorporated an entire archive of mostly analogue media into the film, from private and public sources, and these carry forward the “secret document” from the past into a potentially transformed future. Tokens from the media realm are spread out again and again, either on a light-table or against a monochrome background, and, linked more or less loosely to the central historical event, create a rhizomatic underscoring of the documentary constellation. Colour photographs from Zaatari’s childhood, for example, showing him in Saida Secondary School’s patio, are utterly evocatively of a sheltered garden idyll. A black-and-white photo of curious onlookers staring at the destroyed school building, an image which the film persistently zooms in on, evoking something along the lines of a more profound historical substrate. Towards the end of the film, we learn that Zaatari took many photographs of the devastation around the time it occurred–on Sunday excursions to the sites marked by the war. That episode is in turn elucidated in the diary kept by Zaatari’s brother, another analogue medium, in which a newspaper photo of an Israeli fighter jet appears alongside the written entries. However the (painstakingly documented) impressions of the catastrophe do not entirely dominate the mix of elements, for more “cheery” everyday artefacts also appear: we see a quarter-inch tape being fitted into a tape recorder model that was widespread at the time, which then plays a nonchalant Françoise Hardy song. Or, right at the start, shots with a strong haptic sense, leafing through Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s Le Petit Prince, deployed here not merely as a sentimental classic children’s book but instead as a multi-faceted historic resonating body, chiming with Saint-Exupéry’s own passion for flying, his bustling energy in the midst of the chaos of war right through to his crash or disappearance in the Mediterranean.3

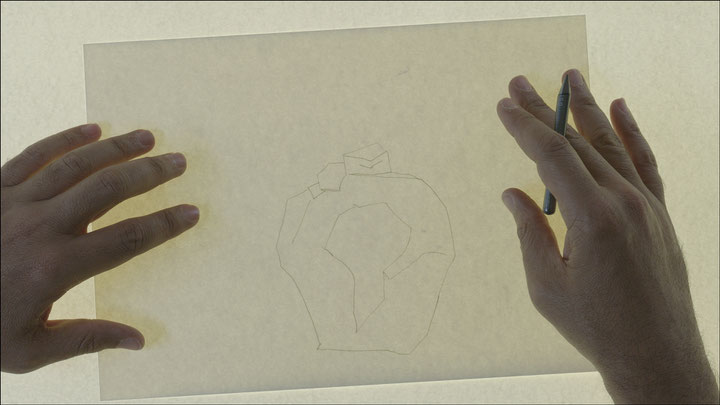

Yet the media arsenal laid out in the film also becomes operative in a different sense. We see paper planes being drawn on a white sheet of paper–followed by similar planes being constructed by folding paper, and then suddenly mutating into (hallucinated) jet-powered flying devices shooting out over the city towards the Mediterranean. At these points, Letter to a Refusing Pilot soars to surreal heights as if it had to or rather could only respond to the trauma unleashed back then with a highly artificial use of contemporary media dispositives. Repeatedly deployed high-frequency tones create an extremely “uncanny” impact, suggesting the catastrophic reverberation of the past, as if more acute noise interference were the only way to cope with this. This is also expressed in the demonstrative, bustling deployment of an analogue microphone, which records–and this comes as no surprise–the cacophonic din of jet fighters.

The film does not however restrict itself to unfurling documentary media technologies connotated as highly “retro”. Semi-fictitious scenes focusing on three pupils currently attending Saida Secondary School are also woven into the work; they clamber up onto a roof after classes and from that vantage point launch the aforementioned paper planes, made from folded pages ripped from their school books. And then there is also the slow circling around an abstract sculpture in the school patio, edited with an incantatory soundtrack: scarred by multiple cuts and scratches and with a large hole at its centre, this angular plastic form was created by Lebanese artist Alfred Basbou. The sculpture, erected in the school yard in 1971, was one of the first modern artworks that Zaatari encountered in his younger days, before he began his career as an artist.4

Here once again we come full circle, closing the loop of historical and autobiographic elements, of (earlier) experiences and (subsequent) montage components–giving shape to the recalcitrant trope of a letter whose destination only becomes apparent in the course of the narrative. A “missive” that is a secret file to be opened anew over and over again.

Translated by Helen Ferguson

1 On the eponymous installation, which also comprises a second video component and one single cinema seat, c.f. Kaelen Wilson-Goldie, “The Archaeology of Rumour”, in: Akram Zaatari – Letter to a Refusing Pilot, exhibition brochure.

2 C.f. Wilson-Goldie, loc. cit.; Seth Anziska, Letter to a Refusing Pilot, in: Letter to a Refusing Pilot, exhibition brochure; also Avihai Becker, “Why We Refused”, in: HAARETZ, 25th September 2002; www.haaretz.com/why-we-refused-1.33287

3 C.f. Sam Bardaouil/Till Fellrath, “What’s in a Letter? (Curator’s Word)”, in: Akram Zaatari – Letter to a Refusing Pilot, exhibition folder.

4 C.f. the fragmentary notes in Letter to a Refusing Pilot, exhibition brochure.