DIY (do-it-yourself)has taken on an expanded meaning beyond re-appropriating communication and media typical for underground cultural movements since the seventies. DIY has been extended by the so-called ‘bedroom generation’ during the nineties, metaphorically opening its bedroom walls to the digitally connected world. Twenty years later the same and the subsequent generations seem to be trapped in an endless technologically-driven self-referential narrative. Furthermore, the virtual disappearance of the walls has been conceptually replaced by the borders of the screen to which they’re constantly referring. The previous ability to question dominant cultural code and and enable alternative ‘processes’, has been obfuscated by the easiness and almost instantness of producing virtual and physical products. This as generated an vacuous loop of self-gratification. Confronting the media strategies of contemporary DIY is then necessary in order to break out of this loop and find again a strategic perspective.

Personal Content: Networked Zines VS. Images Zines

Let’s take one of the most classic products of DIY publishing: the zine. Zines as we know them were created in the sixties thanks to the spread of the mimeograph machine allowing self-publishing by diverse groups, from science fiction fans in United States to political opposition groups behind the Iron Curtain. In the seventies the punk movement started to use them fully, as a proper medium, encouraging the networking and the re-appropriation of visual practices, inspiring the mass production of zines in the subsequent decades. Among them is the incredible mail-art zine production meant to establish a network of artists, exhibitions, shared practices and gestures around the world through the postal network. Or the practice of assembling fake magazines (from “Il Male” 1 in the 70s to “The New York Times Special Edition” 2 in late 2000s) triggering controversial social reactions and so rising public awareness about how printed media work.

But if we look at the current printed zine scene, after the internet revolution, there’s an absolute majority of visual, personal zines. In the recent survey book “Behind the Zines” 3 we find dozens of zines whose main editorial strategy seems to become catalogues of images, with certain aesthetics, taste and sometimes interesting visual paths and twists, but still remaining an endless plain sequence of images and very short texts. The potential of inducing social changes and opportunities, opening up paths for agency by the reader, is then largely missed, focusing on the product appeal and becoming then more “self-gratification” motivation.

And although some zines now seems interested in processes that can be triggered by readers, there are rare exceptions. For example, among the most recent ‘visual’ zines, there’s a new one called “City Strips” and its issue #1 titled “The Amazing City” 4 is comprised exclusively of panels from the Amazing Spiderman series in NYC, from 1963 to 1974, which is comprised exclusively of panels from the Amazing Spiderman series in NYC, from 1963 to 1974, reconstructing the view of the city in that years through silent comic panels depicting representing architectural elements. In its own silent narrative, it’s definitely inspiring readers to re-appropriate images, defining their own consistent algorithm of selection and re-assemblage from celebrated copyright protected comics with a broader scope than just collecting them.

Personal Collection: DIY Book Scanner VS. 3D Printed Objects

In the ‘digitising everything’ collective hysteria which aims to have every conceivable cultural object available at our fingertips through any personal screen, there are at least two different perspectives: digitise to share and digitise to produce. One recent very symbolic development is an open source hardware tool for scanning: the so-called DIY book scanner 6, which is made clearly made to share. A community of 4.000 people is developing and documenting hundreds of variations of this fast book scanners made mainly with cameras (much faster than the moving light and CCDs used in classic flatbed scanners), sophisticated free software, Rasperry Pi boards and structures made out of cheap parts of wood and metal. In their most sophisticated versions they can scan a 150 pages paperback book in less than 15 minutes and eventually make the text searchable with more patient and software-assisted effort. This tool is meant to be an instrument to construct your own digital library and to share it with anybody at any level, explicitly contrasting the current logic of commercial cloud-based service to decide what type of content you’d be allowed to buy. DIY scanning and sharing of publications are an intimate act and there’s a quite large scene made by counter-cultural and political hackers that are actively facilitating the re-appropriation of the elements of libraries, including historical counter-cultural ones like leftist archives and anarchist documentation centres. Furthermore the sharing of the scanned materials can be done publicly through open platforms like archive.org, or deciding and planning which “digital territories” will be able to personally access them.

On the other end the 3D printer is instead intrinsically built to produce. There’s still a huge liberating potential in the enabling of personal manufacturing: it’d would eventually empower the single person to break the laws centralised and controlled production of physical goods, being able to create what is needed in a single piece (vs. mass production with its consequent mass created waste), or what is needed by local communities instead of thinking in terms of global markets. However, this perspective remains largely unrealized.

In fact there’s a massive amount of objects meant to satisfy, again, this self-gratification loop. The process in this case, meant as re-appropriation, manipulation and production is usually overcome by aesthetic fascination, in a looping stupor of the “objet trouvé” which slowly materialises in front of our eyes during its printing process. So we can find plenty of examples of 3D printers used to make extremely refined objects, aimed to pure aesthetic enjoyment. The Japanese artist Aki Inomata well represents this approach, in his series “Why Not Hand Over a ‘Shelter’ to Hermit Crabs?” 6 where he prints in 3D transparent shelters for crabs which incorporate iconic cities’ architectures. The ‘craft’ element in 3D printing is mostly unavoidable, but here (and often in so many 3D printing-based projects) is where it starts and ends, leaving the very potential of this technology, which is of being networked and infinitely programmable, mainly unexplored.

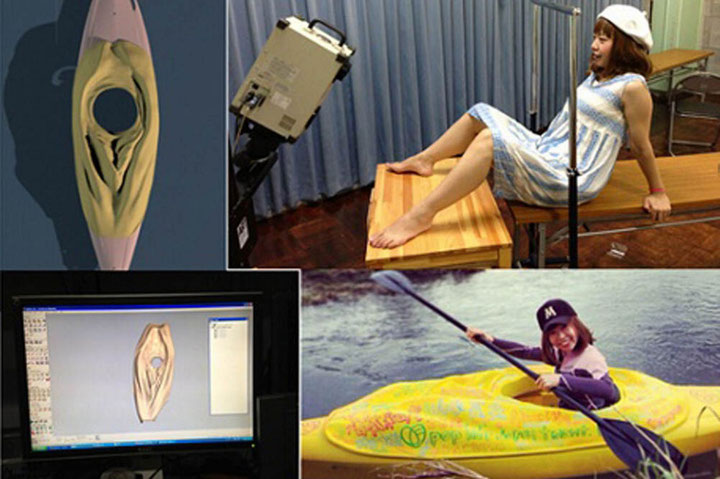

But there are exceptions. “The Free Universal construction kit” 7 by Golan Levin, for example, is empowering users to combine incompatible toy construction kits from different industrial copyrighted ones, establishing an open platform to collectively overcome corporate imposed limits, sharing the results. But also the conceptual work of the Japanese artist Megumi Igarashi, aka Rokudenashiko uses 3D printing to manufacture a product with controversial meanings. Her project “3D MK Boat” 8 consisted in printing in 3D several objects (including a usable kayak) with the shape of her own vagina. She’s implicitly inviting women to replicate what she did, enhancing the abstract geometric aesthetic of the body and pitting it against the absurd Japanese obscene laws (she has been even arrested and then released a couple of days later).

In both these projects, the networked process is indistinguishable from the crafted art object, which finally becomes a proper medium of communication to embody physical and cultural contradictions. Here “creating” a three-dimensional object from an abstract descriptive computer file is not ending with short lasting ecstatic contemplation of the just produced object, but it’s a process instigating other processes, acts, gestures and the evolution of the embodied cultural meanings of object itself.

Personal Image: DIY CCTV Camera Resistance VS. Selfies

Another crucial aspect of the personal information environment is the digitalisation of our own faces. In the ‘digitising everything’ trend, face is a quite sensitive element, as it’s our most private and at the same time most public part of our body. Nowadays it’s even more public than ever, with the extreme proliferations of surveillance cameras that record and increasingly detect and recognise our facial biometric data.

Despite a de facto social acceptance of cameras all over public and private spaces, there are still gestures of resistance, especially in the art world. Ai Wei Wei, for example, in 2013 published a short visual manual about “how to block a surveillance camera” 9 with detailed instructions about building a DIY device that would have let people to spray paint on camera’s optics without being exposed and recorded. And in an even more radical gesture, Leo Selvaggio has started the “URME Surveillance Project,” 10 where he makes and sells at production cost rubber masks of his own face. The challenge then is to be detected and recorded in plenty of places sometimes in the very same moment and in the same space, putting the control paradigm literally out of control.

The portrait has always been a mirror of our presumed superior image (compared to animals, for example), and now it’s more and more dissolving in recombinable pixels. The phenomenon of selfies, in fact, seems to be absolutely iconic of the “me me me” generation, seemingly more interested in being recognized from the world as ‘cool’ and trapped in more and more suffocating self-gratification loops (which indeed are at the core of any social network). In the selfie, the portrait becomes immediate, endlessly repeatable, replicable and enjoyable, especially when it’s then part of the (less and less controllable) cloud.

Self-gratification loops are triggering various digital obsessions. Psychologist define this kind of loops “operant conditioning’ 11. It’s about how what we do depends on either the reward (or the punishment) of what we have done last time (which is indeed a seminal concept in behaviourism). Experiments with animals prove that if they’re rewarded only sometimes and at random intervals they’re way more motivated to work hard than if they’re having regular rewards. It’s what is defined as “variable interval reinforcement schedule.” 12 The intrinsic logic is that even without knowing when and if the next reward will arrive the subject is motivated to work hard longer because “next time” should still be the right one, since no evidence can definitely prove that rewards have been stopped altogether. So we can become trapped in looking for a reward in the next perfect selfie, or in the next fascinating 3D printed object, or in the next image among the many printed in a zine (as well as in the next Facebook post, email, news, etc.).

Selfies can also be treated with a different approach, closer to the personal history through self-portraits than to the disposable quick shots with a smile/grimace. Japanese artist Chino Otsuka, for example, makes this practice a surreal one in her series “Imagine Finding Me.” 13 Here she modifies with Photoshop pictures of her as a kid, seemingly integrating a recent picture of her. The visual result is impressive and destabilising, as she can confront herself with memories in the same photographic and visual space, as if she was physically able to meet her own past. This photographic historical paradox pushes us to reflect on the very nature of the representation in portraits and the implicit meanings that can be carried within pictures. Furthermore the processual nature of the composition gives space to other possible strategies to be shared and widely applied (what would happen if people started to modify pictures creating thousands or millions of such paradoxes?). It can be referred to a famous quote by Brian Eno is: “stop thinking about artworks as objects, and start thinking about them as triggers of experience.”

Conclusion

These comparisons between different artist’s printed products, scanning vs. printing devices, and among self representation mechanisms can be abstracted to a higher level. It’d be surely worth considering how much personal information we just give away to corporations without even being able to retrieve them after a trivial technical problem. Giving up the chance to enable ‘processes’ in exchange of ‘self-gratification rewards’, means embracing on one side the corporate cloud oligarchy in its multiple embodiments and on the other side the serial digital craft, ready to suck, chew and metabolise our own data in slick elegance. Even at the abstract technical level, there are still other forms of resistance, like Danja Vasiliev’s “Superglue” 14 project of a simple visual web authoring and almost plug-and-play personal server toolkit which would finally let you host your online data in our own physical space.

Together with the above mentioned shared projects and techniques it could significantly contribute to focus on the processes involved in our digital gestures and refuse the seductive laziness to receive everything we need digitally and emotionally through obscure remote services. If the virtual windows of the early internet personal world have mostly become global virtual mirrors, perennially reflecting our gestures and manifesting within the giant collective cloud, we’d reclaim our right to select and share only the data and the culture we want to share (from the present and the past), reinforcing our own networks and finally enabling meaningful processes that would start making significant cultural and social changes.

[1] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Il_Male

[2] http://www.nytimes-se.com

[3] http://shop.gestalten.com/behind-the-zines.html

[4] http://citystrips.co.uk/post/73760610288/issue-1-the-amazing-city-february-2014-32-pages

[5] http://www.diybookscanner.org

[6] http://www.aki-inomata.com/works/hermit/

[7] http://fffff.at/free-universal-construction-kit/

[8] http://6d745.com/gallery/

[9] http://www.brainpickings.org/index.php/2013/07/31/ai-weiwei-cctv-camera-do-it/

[10] http://www.urmesurveillance.com

[11] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operant_conditioning

[12] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reinforcement

[13] http://chino.co.uk/gallery/IFM/ifm_1.html

[14] http://www.superglue.it