We are to rethink the 20th anniversary of the public critical access to internet and new media platforms. My argument is that many histories on the topic are histories primarily of West Europe and the First capitalist world; the other half of Europe, the today defunct former Eastern Europe, is seldom mentioned. The reasons of omission of former Eastern Europe and former Yugoslavia could be the perception that stays glued on us and that is formulated as a state of backwardness, namely the former Eastern Europe was in the 1990s in a transition from socialism (not having democracy, freedom and etc.) to the “happy” new world of capitalism. But let me state that in 1994/1995 when a fully commercial usage of the Internet started globally, former Eastern Europeans or former Yugoslavs were shaped and changed by the ways how different subcultural groups and artists working with videos and experimental film could easily embark themselves into the world through net art and activism while leaving aside that outdated world of conservative modernist art. And more, that despite the euphoria of western multiculturalism, cyberfeminists, net activists, etc., could elaborate accurately on the advent of harsh digital divide, processes of exclusion, control, and hegemony that will hit all of us globally in the 21st century.

Finally, a lot can be learned from the Balkan wars in the 1990s in former Yugoslavia. Because of the war in former Yugoslavia (that started in 1991) activists throughout the former Yugoslavia were forced in order to communicate to use new technology and its modes of networking notably the bulletin board system, or BBS, that is seen as a precursor of the World Wide Web; the BBS was used here definitely for political reasons.

I mentioned initially that in the context of critical internet platforms and digital activism many groups and individuals were coming from subculture and alternative contexts in former Yugoslavia, being affiliated with music, theory, critical discourses and video and independent publishing efforts. A similar process happened in the Russian context as well. If we mention just two net art pioneers from Russia, Alexei Shulgin and Olia Lialina, it is telling that Lialina a pioneer Internet artist was initially one of the organizers and later, director of Cine Fantom, an experimental cinema club in Moscow co-founded in 1995 by Lialina with Gleb Aleinikov, Andrej Silvestrov, Boris Ukhananov, Inna Kolosova and others.

On the other side, the 1990s, with the idea of free internet and open access, conveyed a new potentiality for the West as well, but these possibilities vanished expediently after 2001, when we witness that emancipatory potentials of the internet from 1990s are becoming a captive of the capitalist neoliberal market and its ultra-militarized control systems, imposed by multinationals and war-States’ regulations.

Therefore though this text is too short for covering 20 years of history of the digital media and internet in the former Eastern Europe, and though I will focus primarily on former Yugoslavia, I take fully this opportunity, as already in 2004 (when it was the 10th anniversary) Josephine Bosma in an excellent overview of the state of the things titled “Constructing Media Spaces. The novelty of net (worked) art was and is all about access and engagement” referred to the former Eastern European space, in describing the advent of the Internet culture and politics, Bosma referred to former Yugoslavia events with 2 sentences.

I. A history of platforms and events

The event that marked importantly the establishing of social networks and embracing the possibilities of Internet in former Yugoslavia while organizing a physical coming together of dozen of activists, artists, theoreticians, publishers and hackers from former Yugoslavia and globally, was the conference with the title “Beauty and The East” in Ljubljana in 1997. We gathered in Ljubljana by an organizational effort of different positions among them of key importance were the Nettime group (a digital platform and email list), the representatives from the Soros Foundation in Ljubljana, and specifically those involved in its media branch named “Ljudmila.” Nettime was founded in 1995 at a meeting of artists, theorists and media activists at the Venice Biennale, and has been recognized as a pioneer platform for building up the discourses of net critique, providing context for the emergence of net art and critical net culture in general. The central person of Nettime at that point (and as well today) was media theorist Geert Lovink, among others involved was notably Pit Schultz and Diana McCarty. From the Ljubljana side a key figure in organizing the conference was Vuk Ćosić.

Mr. Soros, the “Uncle from America” (as we referred to him, while discussing his almost obscene power position in the 1990s in Eastern Europe) funded the conference. Besides the Soros Foundation in Ljubljana, according to Diana M Carty, Press Now and V2 (Rotterdam) also gave money support to the Nettime Conference. On this occasion the Nettime Book of selected texts the ZKP 4 was printed in 10.000 copies. Evening programs, which were widely publicized, covered pirate radio, lectures by Peter Lamborn Wilson and Critical Art Ensemble, and an all-night party with various D.J.s held in the K4, club in the center of the city. The conference presented positions that I classified, writing about this remarkable event, in two broad lines of thinking and acting in global capitalism at the time and after.

The first line that I called the “Scum of Society Matrix” referred mostly to the positioning of the so called Western participants, proposed autonomy and progressive political option: new autonomous Internet economy and new structures from the appropriation and restructuring of the so-called old ones. It was proposed to go back to writing only (e-mail boxes), as a possible counterculture intercommunication strategy and not simply improving the Internet, i.e., to erase images and to get rid of the pushy internet software industry. In the guise of such utopian mind, it was possible to find genuine strategies for fighting and acting, not just simply reproducing through technology.

The second line that was mostly employed by the former Eastern Europeans, I called the “Matrix of the Monsters.” Why? As Peter Lamborn Wilson, also known as Hakim Bey, in his much attended lecture in Ljubljana in 1997, accurately stated “The second world was erased (we are lucky, aren’t we?) and what is left is the First and Third worlds.”

Is it this not the situation in 2015? Bey continued: “Instead of the Second world, there is a big hole from which one jumps into the Third.” I named this hole and the second direction the “Matrix of the Monsters.” I made as well a direct reference to the general title of the Nettime conference in Ljubljana “Beauty and the East” (a title that was already paraphrasing the known tale “The Beauty and the Beast”).

We the non-existing Second world posed serious political and analytical questions related to the key problem – who are the new and old actors that will construct the “Brave New World?”

“The Monsters,” as I articulated our positions in former Yugoslavia and former Eastern Europe (referring as well to Donna Haraway text “The Promises of Monsters: A Regenerative Politics for Inappropriate/d Others from 1991) insisted on difference, a critical difference within and not as a special classification method marking the process of grounding difference, such as apartheid. The questions that were formed at the discussions exposed the role of the Soros foundation and capital in the former Eastern Europe context, the relation between State and the NGOs, and last but not least, the dialectics of interpretation – who, when and how is allowed to write about the (Art, Culture, Political) History of the once known Eastern Europe.

The conference presented as well what existed already in the space of former Eastern Europe. In Budapest the Fine Art Academy opened a Department of Media Art in 1991, and several years later, in 1996, the Centre for Culture and Communication (C3) was founded in Budapest by Open (Soros) Society Institute to support media artists. In 1995, Ljudmila, the Ljubljana Digital Media Lab in Ljubljana, Slovenia was added to Soros influential media initiatives in the region. However at that point Ljudmila was not conceived as an art project. An important reason for this was, as emphasized by Bosma, the impossibility of receiving funding for art projects, or rather the availability of the funds from the patron of many former Eastern European media labs, George Soros. The E-Lab was founded in Riga, Latvia already in 1996.

In 1997 The Hybrid Workspace organized during the Documenta X (the 10th edition of Documenta) in Kassel was heavily based on the propositions and networking points developed by Nettime. Though Documenta X in Kassel curated by Catherine David seriously reinvented the modernist setting of the Documenta event with the hybrid workshops, it failed to invite important positions from former Eastern Europe. Nevertheless Documenta X hosted Makrolab by Marko Peljhan from Ljubljana.

During the war and nationalism-impregnated 1990s in Croatia the periodical “ARKzine” (a hybrid magazine in which politics, culture, theory and media come together) was a sole example that discussed Central and Eastern Europe NGOs and alternative media interests. The first two, exclusively multimedial cultural spaces in Croatia were Multimedial Institute (Mi2), opened in 1999, and Net Club Mama opened in 2000. MaMa - Multimedia Institute is a net culture club located in Zagreb, founded in 1999 by Tomislav Medak, Marcell Mars, Teodor Celakoski, Petar Milat, Željko Blaće, Vedran Gulin, Vanja Nikolić and others. Ever since it opened in 2000, MaMa has been a meeting point for different local and international communities ranging from political activists, media artists, electronic music makers, theorists, hackers and free software developers, gay and lesbian support groups, to the anime community.

Much earlier than that, the association APSOLUTNO had been founded in 1993 in Novi Sad, Yugoslavia. The production of the association is created through collaboration of its four members ( Zoran Pantelić, Dragan Rakić, Bojana Petrić (and Dragan Miletić from 1995 till 2001) ) and the association was in stark contrast to the claustrophobic context of Serbia. From the association and in relation to APSOLUTNO in the end of the 1990s in Novi Sad an independent organization known as New Media Center_kuda.org was established. It brought together artists, theoreticians, media activists, researchers and the wider public in the field of Information and Communication Technologies.

II. The war in former Yugoslavia and the BBS

Not only that the war started in former Yugoslavia in 1991 as being announced literally on television but it demonstrated the essential impact of new media technology for activists.

The Slovenian war that was first in a long sequel of wars in the Balkans started as a “fuckingly” disturbing Jean Baudrillard’s theory lesson on the function of television in capitalism and what will be it usage in practice. I was breast feeding my son in 1991 when the prime time news anchorwoman stated that the war started in Slovenia.

Vesna Janković, a founding member of the Antiwar Campaign Croatia (ARK) and the founder and editor of ARKzine (1992-1998), writes that “in the autumn of 1991 the telephone lines between Croatia and Serbia were cut. Indeed, new communication technologies, as a distinct constitutive element of new transnational movements, played an important role in the former-Yugoslav context as well. Maintaining communication between anti-war groups was one of the priorities of peace work, but this was increasingly difficult from autumn 1991 because of the damaged post and telephone lines between Serbia and Croatia. Eric Bachman, long term peace activist, involved in former Yugoslav anti-war organizing from the very beginning as a nonviolent trainer and supporter, suggested a (globally) new technological solution – establishment of local BBS (Bulletin Board System) which would be connected through the server in Germany. At the beginning of 1992, the first modem was attached to the computer in Antiwar Campaign office and BBS ZaMir (For Peace) Zagreb was formed. ZaMir Belgrade and ZaMir Ljubljana followed, and a transnational electronic network connecting post-Yugoslav peace, women’s and human rights groups was born. By 1996 ZaMir had seven nodes (Sarajevo, Pristina, Tuzla and Pakrac, in addition to those already mentioned) and several thousand users. It became a firmly established transnational communication space, linking regional activists with each other and the world.” (Janković)

A bulletin board system, or BBS, is a computer server running custom software that allows users to connect to the system using a terminal program. The BBS is in many ways a precursor to the modern form of the World Wide Web, social networks and other aspects of the Internet.

Vesna Janković asks in 2013, when elaborating on the 1990s, if we “can talk about the emergence of new political subject and new political arena? What is the impact of new electronic communications on organizational forms and structures of transnational organizing? What is the impact of transnational activism on national politics? And last, but not least what a semi-periphery (that means the former Yugoslavia space) has to say about it?”

III. The re-politicization of technology

The relation of new forms of subjectivity towards capital is a process of establishing a set of strategies to dismantle mechanisms of exploitation, racialization, and dispossession. Donna Haraway’s seminal text “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century,” published for the first time in 1985 (in 2015 it is the manifesto 30th anniversary) reinvented the paradigm of the cyborg. Haraway’s cyborg-theory, that was rebuilt further in the 1990s with Trinh T. Minh-ha’s paradigm of the inappropriate/ed other, significantly re-articulates the problematic of material-semiotic (sex, gender, technology, democracy and emancipation) in our contemporaneity. The results are new directions within feminism and how to connect them with new media technology and theory, politics and subjectivity in the time of global capitalism. In short, in the present moment, we have to rearticulate again the relations between the First, Second and Third Worlds and the relations of technology to what are to be conceptualized as subjects, objects and abjects.

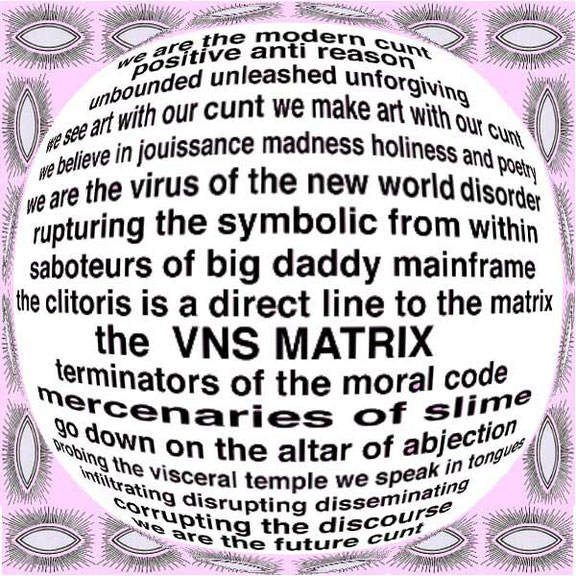

The all-female artist and activist collective VNS Matrix (“VeNuS” Matrix) in Adelaide, Australia may have been the first to employ the term with their 1991 billboard manifesto, “A Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century.” In 1994 the conference “Seduced and Abandoned: The Body in the Virtual World” organized in London theorized cyberfeminism as a derivative of Haraway’s cyborg feminism. Ten years after, the ISEA 2004 meeting in Helsinki celebrated 10 years of Cyberfeminist Theory.

I organized in 1999 as part of the International Festival of Computer Arts in Maribor, Slovenia, an international conference while publishing a book edited in collaboration with Adele Eisenstein “The Spectralization of Technology: From Elsewhere to Cyberfeminism and Back. Institutional Modes of the Cyberworld.” At the conference in Maribor – where among others participants activists from the group Old Boys Network (OBN), founded by Cornelia Sollfrank in 1997 in Berlin took part – we questioned heavily the politics of feminist, post-feminist and cyberfeminist positions from different geopolitical territories. The feminist movement in the 1970s in Belgrade and Zagreb at least shaped a process of radical and avant-garde emancipation, but cyberfeminist movements in Russia and Asia are waiting to be included in the official (Western and White) history of feminism and cyberfeminism, not to mention the important different perspectives of feminism and technology within African and African-American contexts. Thus, it is time to re-write history, re-politicize technology and subjectivities.

REFERENCES:

Josephine Bosma, “Constructing Media Spaces. The novelty of net (worked) art was and is all about access and engagement,” 2004

http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/themes/public_sphere_s/media_spaces/

Marina Gržinić/Aina Šmid http://grzinic-smid.si/

Donna Haraway, Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature (New York; Routledge, 1991.

Olia Lialina http://www.teleportacia.org/

The Spectralization of Technology: From Elsewhere to Cyberfeminism and Back. Institutional, Marina Gržinić and Adele Eisenstein, eds., MKC, Maribor 1999.

Vesna Janković, Post-Yugoslav anti-war movements as an early example of new transnational agency 1 Post-Yugoslav anti-war movements as an early example of new transnational agency, 2013, at http://www.academia.edu/5136376/Post-Yugoslav

Nettime reader, conference Beauty and the East, ZKP 4, 1997 at http://www.ljudmila.org/nettime/zkp4/toc.htm