Issue 4/2015 - Kiev, Moscow and Beyond

Real Socialism Vanquished?

Owen Hatherley and Agata Pyzik discuss various aspects of post-communist history, politics and art

What shape does the communist legacy currently assume in the various countries of the former Eastern Bloc? What kind of reverberations does real socialism still trigger a good 25 years after the fall of the Iron Curtain? What kind of hindsight appraisals dominate in the East and the West? Which barriers has it been possible to overcome in the cultural realm, either in the field of architecture or in popular culture, and which have proved insurmountable? Owen Hatherley and Agata Pyzik, who have addressed various aspects of post-communist history, politics and art in their books, address this nexus of questions in their dialogue.

Owen Hatherley: In your book Poor but Sexy 1, your arguments about culture and life under “real socialism” seem aimed equally at the Western left and Eastern European liberals. What exactly do you think each of these has wrong and why?

Agata Pyzik: I don’t think “liberal” exhausts the target of my critiques! Not everything works according to those ideological boxes. Especially after I started living in the West, which was at the beginning of 2010, I realized that political notions in the former communist east and west didn't delineate exactly the same things. For instance, in almost every respect the Polish or other Eastern European right-wing, conservative side was right-wing and conservative to a degree which would be rather exotic in Western countries. At the same time, in terms of economic ideas, I found that regardless of the political option they subscribed to, everybody everywhere embraced radical neoliberalism and the free market, and put the well-being of businesses above that of their citizens.

If there's something of a critique of the liberal outlook especially in my view of how things could've gone for the former Soviet Bloc after the 1989/1991 changes, it's because democratic forces, liberal opposition and the intelligentsia, when they took power, made the point of their whole existence promising a radically better future for the people and distinguishing positively from the past. But it soon turned out that in this new liberal-friendly Poland, certain people were seen well and certain others were not – for instance, the working classes, who were dependent on Communist-era infrastructure, industry and agriculture, were massively let down in favor of private businesses, tacky suits and enigmatic “entrepreneurialism.” The intelligentsia born and bred during the communist era, despite or maybe because of their noble ideas of “freedom,” simply rejected the whole socialist project as totalitarian, and together with it the people who were dependent on it.

But I also realized that what the Western Marxist left was cherishing as “socialism” or even “full communism” had in turn almost nothing in common with my personal experience of real socialism (I was born in 1983, but still have a very vivid memory of those six years) or that of anybody who lived in the Soviet Bloc. Their version of communism was an idealized version of the Bolshevik revolution, with everything that happened after 1929 being rejected and condemned as reactionary. Where does it put us, people who lived under this system for another 60 years (or less in the case of e.g. Poland)?

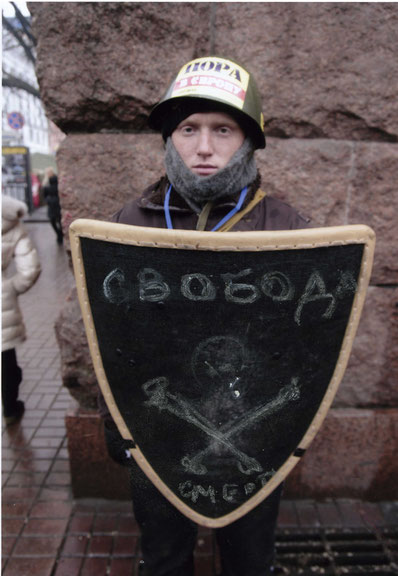

I think it's funny that those two groups, right-thinking Americanized liberals and edgy radical leftists, would agree on this one. In 1989 the radical left even thought that the collapse of the Soviet Union was essentially “good” for the left, because after that real, unscathed communism would emerge purer and better. And if anything, my studies of real socialism taught me that there's no such thing as “pure” leftism and there's no point in waiting for the perfect conditions for the revolution to come. I also have a problem with the patronizing way some Western liberals praised the Maidan revolution, seeing it only as a positive emancipation towards becoming part of the fantasy “West” and willfully ignoring the presence of the nationalist right in it. Now it's taking its toll by exacerbating the preexisting discrepancies between the east and the west of Ukraine. It seems that when the war in Donbass, hopefully, ends, Ukraine will become just another peripheral capitalist state ruled by the conservative right. This is fair enough, but to see it as a great success?

Could things have gone differently after 1991? I don't know. I think the ideology of real socialism had this negative effect on people, that it has made them both cynical and single-minded. When Marxism-Leninism was a ruling doctrine in the Soviet Bloc, then any idea of Marxism or leftism was ridiculed. Everybody knew the party was telling them lies, so when the system collapsed, nobody was taking it seriously, so it couldn't become a weapon against the negative effects of capitalism. On the other hand, the situation in which you're not encouraged to criticize the ruling communist ideology persisted, in this sense that now this ideology is blatant nationalism and “traditional values.” Because the Soviet system ceased to be revolutionary from quite early on and encouraged conformist behavior, its effects are still weighing upon us as nations. If I could point out what is the greatest problem politically, and a challenge in today's Eastern Europe, it's total indifference. The numbers of people voting are tiny, we live in completely post-political societies in which people no longer believe that representative democracy, so hard won, has any influence on their lives.

In my book I tried to show how in people’s daily experience the system wasn't strictly the “totalitarian” caricature it's being painted as by liberal pundits or that this word really doesn't describe the kind of mark it left on people's memory. Real socialism, under its many guises, produced at times extremely interesting culture, great art, film, literature or science. We know also that some of that greatness happened almost despite it, artists were censored and repressed and the daily reality of Soviet artistic or film production wasn't Tarkovsky's masterpieces but tacky comedies. I just want to state that there are many ways in which one system can express itself, and many people describe real socialism as if its bad outcomes were already programmed in it, which is unfair.

Hatherley: Pop culture is a big part of your book and your work in general – music, fashion, magazines. In which ways do you think these were different in Poland and elsewhere at the same time?

Pyzik: As I mentioned earlier, to me real socialism was a place for developing many interesting, original ideas. If it wasn't, you wouldn't have so much interest in socialist art, film or science as you do today. In my book, I also tried to answer the question about the decline in the quality of artistic production after the Soviet Bloc collapse. Why, although now any artistic expression is possible without censorship, have former socialist countries stopped producing masterpieces or speaking in a universal language that could be understood everywhere?

One of the reasons popular culture was so unique under communism is because it was created, as it were, against pop culture in the capitalist West. I became fascinated with this idea – how can popular culture function within a non-capitalist economy, given that it is a function of the fast-paced changeability of the free market? The answer to that is complex. After the years of Stalinism and post-war austerity, the “Thaw” happened, and the authorities across the Bloc, cynically or not, agreed that some kind of opening towards the West and some freedom was necessary. They also felt there was a need to indulge the young generation – “the future of socialism”, after all – a little, including their desire to have consumer goods and behave like their Western counterparts. So they gave them, albeit heavily controlled, rock music, magazines, sex. At the same time, they tried to discourage people from simply copying Western trends, and ridiculed the Western “hipster.”

Art created in such forbidding conditions turned out to be quite noble and with a certain poise. People listened to jazz rather than pop and tried hard to obtain the cool look of their Western counterparts, but without their goods or money. It created a necessity for so-called “applied fantastic,” a term I lifted from the Polish-Jewish writer Leopold Tyrmand. He hated everything about communist Poland, considered it grey and soul-destroying, was a purveyor of jazz and sartorialism in 1950s Warsaw, and in the 60s he left for America and become a rather boring, conservative writer. He was wrong on many things, had contempt for workers and was frequently sexist, but I appreciated his recognition of fashion and pop culture, and realized they were essential in shaping people's aspirations during communism and after its end as well. But because it was only a certain “fantasy” of the West, it ascribed a lot of “magical” features to it that it certainly didn't possess. Before people had to “make their own fun”; with capitalism it has all become a question of money, not fantasy. The fantasy of the West has met its “reality,” and it wasn't fun. Let's also remember how harsh living conditions became when the greatest economic depression in history hit the post-USSR in the 1990s and when class inequalities emerged. These weren't the greatest conditions to create culture.

As for why we ceased to produce masterpieces, the reason is simple – art lost its state financing after the collapse of communism, and with it the whole infrastructure that allowed opulent productions of Tarkovsky or Alexei German, avant-garde animation alongside those not completely charmless silly comedies I mentioned. Art suddenly had to become commercial and produce income. There was also no longer any place for moral ambivalence. Some of the greatest Polish films of that era take their power from a real sense of ambivalence and doubt – not only to fool the censor, but there's real doubt, as in “thinking doubt”, an air of ambiguity about the reality that surrounds us. It is no coincidence that e.g. so-called “chernukha”, i.e. the super-dark, pessimistic style in Soviet cinema, exploded precisely in the late Gorbachevian 1980s. Not because the late 80s was the darkest period in the Soviet history, far from it, but because you could finally talk openly about those things. Today such dark social realism is being rejected, because now we supposedly live in the free world, so there's no longer a need for being critical. This self-censorship seriously limited our art's capacity to tell the story of the last 25 years of transition to capitalism.

Hatherley: The “decommunization laws” in Ukraine seem to be partly based on those passed in Poland under the Law and Justice right wing government. Do you think these laws had any effect, negatively and otherwise?

Pyzik: I think in Poland people were always more resentful about Communism, so the introduction of those laws had in general lesser effect and less meaning than in Ukraine where those symbols still carry a lot of weight for lots of people. It makes sense though, given Poland has become a new blueprint, a “success story” that Ukraine obviously wants to model itself after, although it's obviously a very different society. In Poland, if anything, the law was a sad symbol of how we couldn't properly deal with the communist legacy. And let's remember it is not only the legacy of Eastern Europe – it's being dealt with much better in Italy, where the Communist Party was very strong until the 1980s, or in Germany, although the unification wasn't always a perfect process. Germans also opened their Stasi files years ago and it's not a problem anymore. They basically capitalized on it: Berlin is being only made more attractive thanks to its preservation of the GDR past. They listed most of Alexanderplatz years ago, and although they demolished Palast der Republik, nobody tries to rename Karl-Marx Allee or Rosa Luxemburg Platz, and in general they seem much more at ease with their past. Vienna keeps its Red Army memorial in the city center without any controversy. Must this be also a privilege of the Western countries that the past is less traumatic? Or do they perhaps survive because those countries still have a labor movement and a sizeable radical left?

Those symbols and names do matter however in post-Communist countries. There, political parties hijacked the past and try to make political capital on their anti-Communism. In discussions over Russian annexation and war interventions in Ukraine, all too often it is almost suggested that it's the Cold War and the successor state to the USSR trying to subjugate Ukraine again. This somehow forgets Russia is a super-capitalist country today, and even if it tries to keep its political influence over neighboring countries, it's definitely not because they plan to restore the Soviet Union.

If anything, communist symbols in a country like Russia, where the streets are full of them, are just decoration, they're absolutely meaningless. Maybe that's why nobody sees any threat in them. If, say, the Communist Party in Russia became a real threat to corruption or big business, and people gathered around those symbols, you could be sure that they wouldn't last long. And many of them are already silently being removed and replaced with statues of tsars or church officials. Only if communist symbols start to stand for something real do they become a problem. In a country like Ukraine, they stand for ethnic intolerance between the east and west. In Poland, where they are completely dead, their destruction serves both neoliberals and the right. It stands for a symbol of the hated communist occupation, which persecuted the church, and as a symbol of hated Russia, which apparently wants to attack us. For both they seem to be more about contemporary Russia than about the past.

Would you say that the Western left has it easier in restoring any positive connotations to Marxism? You definitely can embrace leftist ideas from the past without feeling guilty or fearing that somebody will call you a Gulag-apologist (as happened to me many times). At the same time, the British left rejected Soviet-Bloc-style communism after learning of Stalinist crimes in 1956 and never deemed “real socialism” worthy of attention again, but shifted its attention to China and Cuba instead. I think this was done unjustly, because precisely then people under communist rule in Eastern Europe enjoyed greater freedoms, improved living standards and the most interesting culture. What was decisive for you to change your mind and decide “real socialism” was interesting after all? Do you think that perhaps the Western left is also disadvantaged, but in a different way?

Hatherley: First of all, I'm not really sure if it is so rare for any Western leftist to be accused of “Gulag apologism” if they suggest that not everything that happened in a Communist-ruled country between 1917 and 1991 was utterly evil. I've seen it a fair bit, though it's usually more a matter of Internet comments than of being directly confronted. I recently chaired a meeting with Kristin Ross on the Paris Commune and someone in the audience was upset we were too sympathetic to the Communards, who obviously deserved to be slaughtered because they'd taken up arms against the state and so forth. In fact I think it's partly because of fear that someone will call you a “tankie” or assume that you think what Stalin did was somehow acceptable (as a trade off, omelette-making or whatever), that makes Westerners avoid thinking much about what happened between, say, 1924 and 1989. So in the coffee table books on communist architecture I know you like so much, you at once condemn the regime totally and then enjoy, rather dishonestly, the buildings and monuments it produced.

So the Western leftist political tradition I was brought up in – Trotskyism, a tradition that didn't exist in the Soviet Union after 1936 largely because nearly all Trotskyists were killed – basically saw everything after the final suppression of the Left Opposition in 1927 as a series of heroic people's uprisings (Berlin 1953, Budapest 1956, Novocherkassk 1962, Czechoslovakia 1968, Gdansk 1970 and 1980-1) and had almost zero interest in what happened in between, which was all just “Stalinism” and nothing to do with us. Conversely, the 1920s were elevated into a golden age, although by 1923 free political discussion was practically over, and by 1929 the room for cultural expression was already very circumscribed. A society like Yugoslavia in the '60s and '70s was actually probably much freer and much closer to Marxist ideals than the Soviet '20s, but you couldn't talk about it, because it was tainted as “Stalinist.”

Looked at coldly, it makes no sense that only after 1956 the Soviet Union was beyond the pale for the Western left, given that it probably had its greatest prestige in, say, 1936 or 1945. In the British Communist Party, Hungary and the “secret speech” were the last straw for a lot of people (like the Communist Party Historians Group, E. P. Thompson and Christopher Hill and Raymond Williams, etc.) who had tolerated things they knew were wrong for years before then, and after it they mostly stopped paying attention to the changes that actually did take place in the Soviet sphere. Also, let's face it, the real cultural, social and economic advances in eastern Europe after '56 were pretty similar to those of the West – economic growth, full employment in boring factory jobs, clean and spacious modernist housing, urbanization, class mobility, new wave cinema, abstract painting. It didn't seem like an alternative society, just a slightly different one.

As for me, I didn't come to an interest in “real socialism” from nowhere – I'd written a PhD on the 20s in the USSR and Germany, which meant that I was aware the received ideas on this era were a little shaky. Also, I already had a fairly guilty liking for some of that era's architectural products – I'd seen things like Karl-Marx-Allee, Jested TV tower, the Metro and the Hotel International in Prague and so on and liked them a lot, and rather hoped I'd learn more about the societies that produced such peculiar objects, and whether or not this was connected with the “socialism” they professed.

Pyzik: Your book on the Landscapes of Communism2 made me look at buildings and cities that I feel personally attached to through foreign eyes. I think that you're lucky not to feel like you have to prove anything, fight the anti-communist superego and convince people and can allow yourself just to enjoy those buildings. Do you think that because you have no personal attachment to those places, you can understand them better or that it makes it more difficult? How does post-communist Europe make you feel?

Hatherley: I don't think it is very detached, although I think partisanship on this can be suspicious. I don't hold with apologias for the system or with the idea it was all “totalitarian” from start to finish, and its architecture actually shows just how complex and contradictory a system it was, hardly univocal or unequivocal. Also, it's not always a matter of “enjoying” buildings as such, but about exploring whether or not something happened which was different, not better, not worse, but different, to what took place in Western Europe at the same time. That's where the taxonomy of things the book has (Magistrale, Microrayons, Social Condensers, High-Buildings, Metros, Reconstructions, Improvisations and Memorials) comes from – precisely because these particular forms didn't really exist in the same way in Western Europe or the US at the same time, although even here there are parallels. A lot of what happened, while not exactly “socialist,” is hard to see as “state capitalist” either, but often is the consequences of land nationalization, the fact that you didn't need to maximize profit on a particular piece of land – for instance, both the unusually well-preserved old towns and the spacious high-rise estates come from the same economic fact, the absence of property speculation.

As to what it makes me “feel,” it depends. Karl-Marx-Allee gives a feeling of exhilaration and sublimity, as does the eye for space and skylines that was such a major part of “real socialist” architecture and planning; but at the same time the cynicism of much of it is overpowering, both in horrible, impenetrable nonsense like Ceaușescu's grand projects or the unbelievable spatial inequalities in a city like Tbilisi, where the “modernization” just runs out half-way down the street, and the “European'”projects collapse into chaotic pavements, crumbling, semi-derelict tenements and drastic self-built extensions.

Maybe because I write myself (and yourself) into the book, my personal engagement with it or otherwise becomes an issue. If I'd just written a straight documentary history of this stuff – like, say, Anders Åman's book on architecture in Eastern Europe under Stalin3 – it wouldn't be a question, because what Åman “feels” is irrelevant to his argument. It's relevant to mine because architecture is an experiential thing, and so it's more interesting to me to write about how you feel it as you're walking, talking, touching and smelling it. Otherwise you might as well just do it via Google Maps. I'm also not a blank slate here but I've got my own emotional/political investment in it because, being born into the faith, I was surrounded with the books and the iconography of Marx, Engels, Lenin (and Trotsky). My Dad had a bust of Lenin on his bookcase when I was growing up, my Mum a huge poster of Trotsky. They obviously thought the revolution was betrayed some time in the '20s and didn't defend it since then, but it's still the same family, as it were, even if a particularly estranged relative. Also, I have a certain personal attachment to these places when I'm writing up the walks later, because it's things we've seen together.

Of course that isn't the same “feeling” as someone who has grown up among them, and on that level obviously there are nuances and associations that I'm going to miss, but what do we then do, decide that only people who've grown up in Florence (preferably in the fifteenth century) can write about the Renaissance? I mean, Pevsner wasn't English but I wouldn't decide that Simon Jenkins understood English architecture better because he was.

Pyzik: In the last few years I know you've become engaged in contemporary politics in Eastern Europe in a way you hadn't before – your first book Militant Modernism4 had some rather detached, aesthetic examinations of some of the Soviet avant-garde, but with no references to what is happening there now. Do you think it enriched your way of understanding politics? How do you see the history of the last 25 years of the former East by comparison to Britain, which was your main point of reference (also in the following books on its neoliberal architecture)?

Hatherley: Well on the face of it, the two books you're talking about (A Guide to the New Ruins of Great Britain and A New Kind of Bleak)5 do something similar to Landscapes of Communism in that they're a sort of political history told through buildings, but there's big differences. One is that I'm not so sure I do write about contemporary politics in Eastern Europe at any point, in fact I generally avoid doing so too directly, because I don't have the knowledge in the same way as I do on the UK. It's much less topical – what those two books on the UK are is attempts to intervene into a particular current argument, and specific current policies. I don't think I could do that on the entirety of the ex-communist bloc between East Germany and China even if I wanted to. It's much more about following particular ideas in a circumscribed time period, i.e. up to around 1990, and then testing that against how they feel, look and work in the present.

The relation to my first book is another matter entirely. I'm mildly embarrassed by that book, but actually that's not totally fair. The engagement with the USSR in that book is through Richard Pare's book of photos of 1920s/early 30s buildings, The Lost Vanguard.6 Pare is a great photographer, and the way that these places looked so forlorn, light and optimistic yet rotting to pieces, was rather moving to me, and so I spun some perhaps rather silly speculation around that. What was actually really striking on actually spending much time in these places with you (I'd been to Berlin, Zagreb, Ljubljana, Prague and Budapest, but only the first two of those are really particularly “communist” in their urban landscape) is just how clearly they weren't ruined at all, but used in a quite everyday, mundane fashion. That was if anything more interesting – that this stuff was just part of people's lives, like Victorian housing and public buildings are here.

That doesn't mean I ignore what is happening now, but I've preferred to footnote people who are writing about its contemporary politics rather than try and do so myself. By and large, I think the effects of 1989 were pretty similar in both halves of Europe, in that certain advantages in mobility and freedom of speech were exchanged for a complete evisceration of the social sphere. Britain and Poland are closer in terms of the destruction of the welfare state and the decline in solidarity than Britain and France or Poland and Norway, let's say. In that sense it's actually surprisingly familiar. I mean you've spotted this yourself about, say, Stockholm or Vienna, that they're more “socialist” (albeit in a quite boring way) than Bratislava or Warsaw.

Another question when talking about these places today is the EU. Both the right and left in the UK share a hostility to the EU, and, given the refugee crisis or the treatment of Greece, it's quite hard not to see they have a point. But it's very striking when you're in, say, Katowice or Ostrava that trams, high-rise housing refurbishment, public squares and suchlike always seem to be directly EU funded. You can see why it is considered a “civilizing” influence by many younger people. Those programs are being pared down a lot in the newer Balkan members, and Bulgaria isn't getting the same rather good deal that Poland did. I think it's very telling that places in Ukraine bordering on Poland (Lviv oblast for instance) still see the EU as a savior, despite its treatment of refugees, despite Greece and the troika, etc., because there you have a seemingly similar society where EU integration seems to have made a difference in it becoming cleaner, neater, a more modern, less obviously gangster capitalism than that in Ukraine. Yet the areas of Ukraine that are as close to Bucharest as Lviv is to Warsaw (Odessa oblast, say) don't have a similar idealization of the EU, because Romania is much less hard to sell as a great post-Communist success. There's a lot behind the surface in that which isn't publicized, such as Poland exporting many of its unemployed, or the debt-write-off it got in the early '90s, or the huge infrastructure funding it has received more recently. To the untrained eye, and with the assistance of what you've called “success propaganda,” people are convinced that Poland's apparent success compared with Ukraine (a comparable country, in 1991) is due to anti-Communism, low taxes, liberal employment laws, freedom for small businesses or whatever. Somehow, by knocking down Lenin statues and replacing them with statues of Ukrainian fascist “heroes,” and by cutting taxes and privatizing anything that moves, they, too, might enter the promised land.

Translated by Helen Ferguson

1 Agata Pyzik, Poor but Sexy: Culture Clashes in Europe East and West. Zero Books 2014.

2 Owen Hatherley, Landscapes of Communism: A History Through Buildings. London 2015.

3 C.f. Anders Åman, Architecture and Ideology in Eastern Europe During the Stalin Era: An Aspect of Cold-War History. Cambridge/London 1992.

4 Owen Hatherley, Militant Modernism. Zero Books 2009.

5 Owen Hatherley, A Guide to the New Ruins of Great Britain. London 2011; Owen Hatherley, A New Kind of Bleak: Journeys Through Urban Britain. London 2013.

6 Richard Pare, The Lost Vanguard. Russian Modernist Architecture 1922–1932. New York 2007.