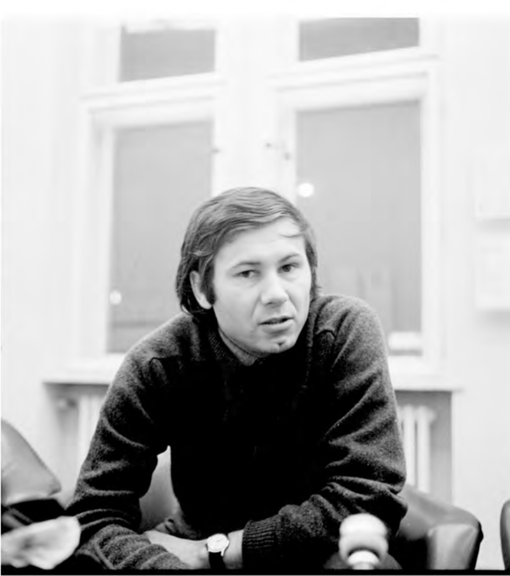

Jesa Denegri has a central role with regard to art from the former Yugoslavia. As a critic and art historian, he observed and influenced above all the generation of the 1970s. His theory of the »other line«, in which he came up with a genealogy of the neo-avant-garde that deviated from canonic models, became an influential factor in recent artistic developments. In the following interview, which took place in February 2007, he recapitulates the way his theory arose, its orientation and application, and the way it has gradually become outdated.

[b]Stevan Vukovic:[/b] Your main art-historical argumentation revolves around the theory of the »other line«. How did you come up with this idea?

[b]Jesa Denegri:[/b] Actually, the way I arrived at this interpretative frame was as follows: in the early 1970s, there were clashes and misunderstandings between then young, upcoming artists and the whole setting in which they were active. The young artists were wondering why they were not being recognized, and why almost no one could figure out what they were doing. And my answer to that was: because you do not have the right historical predecessors.

For the artists, who are just practitioners, this does not have to be obvious, but for the art historian who has been researching different previous epochs in the history of art, it is plain that lines of continuity are extremely important, and that continuity gives legitimacy to those artistic practices which seem to be very new and strange in their phenomenology. But if these practices are coded and interpreted in the right manner, and placed in a diachronic line, they become comprehensible and clearly recognisable. For instance, I learned during my stays in Italy that, when Kounellis exhibits horses in a gallery space, he can do so because there were Alberto Burri and Lucio Fontana before that, and futurism before them. This seems strange at first glance, for their works differ a lot at the level of formal language, but the main ways of understanding art by these artists are related. Fontana is a proponent of spatialism, which means that the space is limitless. Burri argued that any material at all could be used (if one can use a sack, why not a horse?), while the futurists stressed innovation. What I wanted to do was provide the artists of the 1970s with a timeline like this.

In the former Yugoslavia, there were no developed, historical avant-gardes that artists could use as an orientation, and even what did exist was not researched until the 1970s. It happened that this was precisely the time when the work of Bauhaus-student August _ernigoj, the Zenit movement,1 Dragan Aleksic’s »Dada-Tank«2 and the groups Gorgona3 and Exat514 was being reassessed. As I belonged to the group of researchers working on these things, I had direct insights into what one could use to argue for a different historical line in local art that was based on the avant-garde tradition. It appeared to me that there was a set of historical periods that could be lined up according to conceptual similarities; and, in talking with some of the artists that were proponents of the art of the 1970s, I realised that what they appreciated from previous historical periods was not academic modernism, such as the heritage of the Paris school of painting, Picasso, Matisse, Braque: the things that were normative in art academies, art associations etc.. I took the term »otherness« from Michel Tapie, who speaks of the Informel movement as »l’art autre«, and from Pierre Restany, who was interested in »l’autre face d’art«, another face of art, which linked the work of Arman, Tinguely and Klein to Duchamp, and contrasted it with the tradition of Matisse, Braque or Picasso. In a debate that was conducted in Zagreb about Exat, Boris Kelemen used the term »another heritage«. He was referring to works by people like Seissel, who was in Zenit, but represented a form of constructivism.

[b]Vukovic:[/b] You frequently mention the word »ideology« in your writings. What was your ideological standpoint at the time when you came up with the theory of the »other line», and how did it relate to the real political context?

[b]Denegri:[/b] Since my generation grew up under the specific Yugoslav version of state socialism, that is, a system that was not too rigid, but one that did regulate personal and collective behaviour, it appeared to me that one had to stand up for a concept of personal freedom or freedom of the individual that was not restricted with regard to the political system. My position was established as if it did not matter in which social and political setting my practices were taking place. I found a good sentence on that topic in Josip Vanista’s discussion with Marijan Jevsovar: he said that they carried out their art as if they were not living under communism. I did not think that I had to take into account what the official ideology was propagating, nor did I feel an obligation to oppose it. I found enough room for manoeuvre in the field of art, even though I was working at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Belgrade, which was without a doubt an institution that was founded and financed by society. In the complex process of transformation of self-management in socialism, one professional field, such as the field of art history and art criticism, defined as above, was allowed to maintain its professional, moral and political autonomy. And I did not want to betray my vocation, a part of the humanistic set of values that I supported, and use art as a tool to politically delegitimise the regime that I clearly disagreed with. The other danger was becoming fully integrated into the system, something which I constantly avoided. Art made it possible to stay away from both extremes, and that is also one of the reasons why art was so important then, at least visual art, which had a symbolic language that was less explicit than film or literature, for instance. This meant that it was in a position to avoid the critical aspects of the ideological crisis through which socialism was passing. Art, with its international setting, had the capacity to rise above the banal reality of everyday political life – from the time of the establishment of state socialism up to the current transition processes, art has remained the only cause one can really believe in. I am now talking about art in general, but the peripheral artistic practices that I was supporting had perhaps kept, besides a very clear international language, the highest level of moral dignity as well – there were many fewer affairs and sellouts in this type of art, which in that sense benefited from its own marginality. So in the final consequence, this is a political position, even though it did not declare itself in any way in a political sense. It did not articulate itself either as dissident or as supporting the system - instead, it kept to the notion of a high autonomy of art which remains part of the social currents of the times. That is not art out of space and time, but autonomous art whose signs therefore can not easily be transcoded by any one side. That is why I liked hermetic types of languages such as the one Julije Knifer developed; they have the advantage of resisting any type of placement within a political matrix. On the other hand, I felt quite distant from artistic activities such as those of Mica Popovic,5 for example, who painted »Gastarbeiter« (foreign workers) and used allegorical means to criticize state socialism, setting himself up as a tribune of the people, which I found compromising. Some people may say that my position was a very easy one to take - it was much more dangerous to expose one’s text or an exhibition to censorship, or have one’s name as a topic of debate at some committee meeting. But by sticking to high standards in art and criticism, I was able to prevent a situation in which some committee would debate about my work. I worked in the Museum and was in a position to be the curator of many different international shows and international presentations of artists from the region, but I was never forced to frame that in accordance with any political set of values and be a mere executor of a political request. I just had the luck to live in a society in which one could stay away both from political demands and the demands of the market.

[b]Vukovic:[/b] How much was your standpoint influenced and/or called into question by events in 1968 , and were your views shared by the post-1968 artists?

[b]Denegri:[/b] The generation of post-1968 artists, which was the generation I worked with the most, shared with the previous generation - the neo-constructivist artists associated with »New Tendencies«6 - a great mistrust of the aestheticism of mainstream art, which took no ideological position. For Matko Mestrovic, the ideology of his time was based on a belief in a progressive society that would use the achievements of advanced technology to renew the cooperation between artists, designers, architects, creating completely new surroundings that would make possible a more harmonious way of living than egalitarian socialism could. One can find some common points between these cultural practices and those of the so called »Praxis philosophy«,7 which also never doubted the basis of the society that was to grow into »socialism with a human face«. That was an optimal projection, because no one doubted the fact that a better society than the one which really existed here was desirable, although the destructive tendencies of the dissident intellectuals of the time countered all that. The ideology of »New Tendencies« was close to me and, if it answers your question, it was only after 1968 that I found it utterly impossible to support a type of art like this without reservations. The art that came after it was much more interesting in its phenomenological features and meanings than the one before it. The first shock from the field of art came when Germano Celant, whom we knew from »New Tendencies«, which he regularly visited, came back from the United States in 1966 and told us about the writings of Robert Morris, which he was studying at the time. Morris introduced the notion of anti-form, which was to conclude the whole story of minimal art. It was completely unknown to us here. On the other hand, at that time we had Jerzy Grotowski8 performing at a theatre festival in Belgrade, but we could not derive ideas from his performances, and it was through Celant that we realized that arte povera could be a version of what Grotowski was doing in theatre. Celant thought much faster and clearer than other curators of the time, so that he made possible the turn from constructivism, minimalism, and even pop art, towards something much different. Then, between 1966 and 1969, we witnessed quite a number of new practices: arte povera, conceptual art, body art, land art, process art. Suddenly, everything was possible. While »New Tendencies« showed works that still relied on visual perception, on an object that could be in motion, a kinetic object, but still of a material nature, with the advancement of artistic practices in the late sixties we believed in the Marcusean dictum of the power of imagination. There was a huge wave of liberation from all the social and cultural canons, and a trust in the possibility of freedom on every level, both social and individual. But the notion of freedom was differently interpreted by various artists and groups of artists, so that, for instance, members of the OHO group,9 when they got into the list of artists presented on the »Information« exhibition, and then even into the book by Lucy Lippard on the dematerialisation of artistic practices, decided to quit art and form a commune in Sempas. They were still quite idealistic about the context of art, both the political and the institutional one, while, for instance, Goran Trbuljak and Braco Dimitrijevic were aware of the ambivalent nature of the art world. The art world enables the production and promotion of works, but also means an inclusion in the complex network of relationships between institutional frameworks, art criticism and the market; so these artists have actually used institutional mechanisms as material for their work. What was really fascinating for me was the manner in which Dimitrijevic took over Daniel Buren’s basic attitude and principles, using them as a basis to make works with chance passers-by: busts, memorial plates etc... What he actually took from Buren, as he told me in an informal conversation, was the consideration of the context, of the institutional setting, the place where the work of art was installed, while, for instance, I myself, until that moment, had not figured out the full significance of the institutional frame for the reading of art practices presented in it, even though I was working in a very institutionalised place, the Museum of Contemporary Art. A number of artists followed this approach, and the whole issue of the social and institutional framework of art was systematised in the »Edinburgh Statement« of Rasa Todosijevic, and the »General Strike« project by Goran Djordjevic. In the »Edinburgh Statement«, Todosijevic listed all those who profit from art, pointing out all the factors of the art system operative in the setting from which he originated, so that I could also see my place in it. The »General Strike« project finished up the whole story: here it was proven that there couldn’t be any strike, because the artists were inclined to adjust to the system. We called that moment the end of the great utopian idea of total changing a society. Later on, Ilija Soskic gave the change that happened after the late seventies a label that was used for terrorists who have changed their attitudes and repented their deeds – »Pentiti« in Italian. Funnily enough, Achille Benito Oliva himself claimed to be the Iago of the time, as someone who drags another into a crime.

[b]Vukovic:[/b] What are the limitations of, as you once called it, the »ideology of your youth«?

[b]Denegri:[/b] With regard to its interpretative capacity, the art of the eighties was a great test not only for my theory of the »other line«, but also for my general understanding of contemporary art. The 1980 Venice Biennial, with all the textual accompaniment and debates that surrounded it, and before that the 1979 exhibition in Belgrade, curated by Marcia Tucker, featuring »bad painting«, completely puzzled us. We did not know how to read that sort of art. Then we realised that perhaps we had been living too long under the influence of minimal art and Joseph Kosuth’s clean version of conceptual art, and that we had missed seeing that the modernist paradigm was in decline. Coming back from the 1980 Venice Biennial, curated by Achille Bonito Oliva and Harald Szeeman, and reading Oliva’s book »Territorie magico«, which dealt with the ideology of the seventies, coding it in a completely different manner, I had the impression that my theory of the »other line« had to be put aside, as something historically limited that had no interpretative power to deal with current art. At a local level, some projects, like the failed »General Strike of Artists« by Goran Djordjevic, for instance, proved that the type of art we had strongly believed in was on its last legs. But, even though art practices were changing significantly, the theory of the »other line«, with some corrections, was not completely outdated, and, in the historical sense, some international validations show that its explanatory role was justified.

»The ideology of my youth« is an expression that I used when talking about the art of the nineties and my position with regard to it. What I meant was that I was not fully able to participate in the context that was essential for the production of the art of the times with the same level of understanding as in the seventies. Actually, I borrowed it from Carlo Giulio Argan, who used it in an interview for »Moment« magazine during one of his visits to Belgrade, when he was asked about the then very frequently used term of post-modern art. He said that he had grown up with the Bauhaus ideals and the work of Cézanne, and that these had framed his world view, so that he, like me, could not make the jump to Derrida or Lyotard, or, for instance, to Oliva, and switch to a completely different ideology. For me, that meant being reserved with respect to my understanding of the art of the nineties. But in that context, too, I had some parameters linked to the art of the seventies or even earlier, while bearing in mind the differences in these paradigms. This was a defensive formula which was intended to stress the fact that my position in the nineties could not be the same as in earlier periods, and for a multiplicity of reasons: first, the artistic practices had changed; people who were much closer to these practices at a grass-roots level came to participate in the scene, so that I had to confess that I considered my methodology a bit outdated, as well as my way of participating in the scene. So, what I started doing already in the eighties - for instance, when I was invited to curate an exhibition titled »Art in the Midst of the Eighties« - was to refrain from doing it myself and invite other, younger critics, namely Lidija Merenik, Bojana Pejic, Marina Grzinic and Davor Matizevic, to curate it instead of me, in order to learn something from the manner in which they thought and worked. I wanted to provide space for a new generation of critics and curators, and I did the same thing with the generation in the nineties: I opened a space for it to curate on the basis of its own ideology. Some of these people are now the most active on the scene, such as Zoran Eric, Jasmina Cubrilo and Svjetlana Racanovic . But I have never withdrawn from the scene, and even in the nineties we had these furious debates on the Second Modern, between Misko Suvakovic and Branko Dimitrijevic, for instance, to which I did perhaps give an initial impetus. Perhaps it is only in this decade, the beginning of which was marked by »relational aesthetics«10, that I slowly lost track of what is going on - but there are so many younger people to define the art of their times.

[b]Vukovic:[/b] Do you still define your basic position as that of a critic?

[b]Denegri:[/b] Yes, and in saying that I mean that the different institutional obligations I have had in relation to art production in the course of the years of my work as a professional, as a museum curator, editor of magazines, a writer and educator, were basically motivated by my position as a critic. I could describe all these other functions as simply posts, with specific tasks to execute, while the real vocation for me is that of the critic. And it is here that I passionately invest my potential. There are quite a few curators and professors with a very high level of didactic knowledge, but the main question is whether they are being driven by a deeper instinct, a drive, a need to get involved in art, to become deeply involved with it, or whether they just put into practice someone else’s programmes, remaining at the level of simply retelling someone else’s thoughts. The kind of person who does get involved I call a critic, and being a critic is for me a specific vocation. A critic, defined in this way, is not someone who criticises art from a theoretical, aesthetic or art-historical standpoint, someone who judges art from a specific critical position and wants to make it better, or files complaints to the artists. Rather, such critics work very closely with artists and provide their works with an ideology that is not so easily readable in the language of art as such. This kind of definition of the role of the critic in the art world is perhaps characteristic for the time when my professional formation took place, because, before that, a critic was considered to be someone who simply kept track of what was going on in contemporary art and judged if an exhibition was successful or not, wrote about it in the media and took on the role of judge.

1 Named after the avant-garde magazine »Zenit«, founded and edited by Ljubomir Micic. It was published between 1921 and1926, at first in Zagreb, then in Belgrade.

2 Magazine put out by Dragan Aleksic in the 1920s.

3 Group of artists that was active in Zagreb from 1959 to 1966. The group consisted of the artists Marijan Jevsovar, Julije Knifer, Duro Seder, Ivan Kozaric and Josip Vanista, the architect Miljenko Horvat and the art historians Matko Mestrovic and Radosav Putar.

4 Group of artists active in Zagreb from 1950 to 1956. Its members were the architects Bernardo Bernardi, Zdravko Bregovac, Zvonimir Radic, Bozidar Rasica, Vjenceslav Richter and Vladimir Zarahovic, and the painters Vlado Kristl, Ivan Picelj and Aleksandar Srnec.

5 Serbian painter and filmmaker (1923-1996), known above all for his informal period in the 1960s.

6 Artistic movement that put on five international exhibitions in Zagreb from 1961 to 1973; see http://www.msu.hr/msuzbirke_tendencije_e.htm

7 School of philosophy and social science that arose at Zagreb University in the 1960s.

8 Polish director and theatre theorist; for example, see For a Poor Theatre, 1969/2005.

9 Group of artists, writers and experimental filmmakers that, after reistic projects, devoted itself to arte povera; from 1968 it carried out conceptual projects, and later telepathic ones.

10 See Nicolas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics, Paris 1998.