Film, said Marcel Broodthaers once, is by no means intended only for the cinema, at least the way he understood it. And, indeed, the good 35 cinematic works that the Belgian made between 1957 and 1975 aimed at extending aspects of representation and, above all, presentation that took the classical black box into only limited account. These days, many a cinema essentialist would catch their breath at the lack of respect he paid to this historically contingent situation of presentation and viewing. For Broodthaers, film was first of all no more than a logical continuation of language – from the word, objects and images to complete environments. This did not only mean that his films, accompanied for example by specially designed screens and text books, were to circulate as multiples outside genuine cinema settings as well. Broodthaers – perhaps to avoid questions about correct presentation in the first place – also founded his own museum, in which he was able to do as he pleased with cinematic material in a manner befitting his general scepticism with regard to art and institutions.

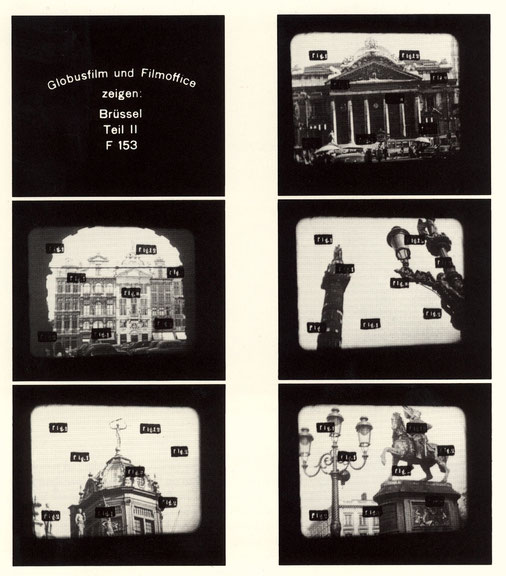

For almost two years (1971/72), the »Section Cinéma« of his Musée d’Art Moderne, Départment des Aigles, was installed in a Düsseldorf cellar. As well as all kinds of sculptural arrangements and wall inscriptions (including his famous »Fig.« numbering that led itself ad absurdum), it also included a presentation niche in which five of his films were projected onto a screen with printing on it. Two of these works – now rarities, like many other screen works by the Belgian since the »Section Cinéma« was closed down – could be seen recently in a different setting in the Galerie Nächst St. Stephan in Vienna. In the exhibition »Riss/Lücke/Scharnier«, »Charlie als Filmstar« and »Brüssel Teil II« form a kind of secret climax that was the culmination of questions posed by the curator/artist Heinrich Dunst about the »distances and disjunctions between what is seen and what is said«. Even though the show drew a wide-ranging, contradictory connecting line from Baldessar to Clegg & Guttmann, from Louise Lawler to Joëlle Tuerlinckx, »the form of representation that is incapable of remaining at the visible or the sayable« (Dunst) seems to be present at its most paradigmatic in Broodthaers’ home-cinema travesty.

»Charlie als Filmstar« and »Brüssel Teil II«, both found-footage works about two-and-a-half minutes in length, use material that is the epitome of all that is artistic anathema to Broodthaers: advertising films, city commercials, promotion of spectacular Hollywood presentations. Both are identified as products of a company called Globusfilm, and thus appear as classical readymades whose commercial character does not at all need to be specially avoided or artistically transformed any more – for example, by the special type of montage. This job is done instead by the manner of projection, that is, by the special screen, which is littered with Broodthaers’ typical markings (»fig. 1«, »fig. 2«, fig. 12« etc.). The striking effect that arises because of this superimposition involves several elements: at first, the writing on the screen remains like a transparent sheet »in front of« the apparent depth of the film image – which seems paradoxical, as the screen is »behind« what is projected on it. At the same time, confusion arises because objects and indexes begin to refer constantly to one another without clear correspondencies ever resulting. And, finally, the repeated changes between the mute presence of the objects and their symbolic eloquence (or the suggestion of this) makes it apparent that it is impossible to trace cinematic events back to »external« patterns of meaning, just as every mode of interpretation always rebounds a little from the raw concreteness of images.

Broodthaers intended the aimless »figuration« (0,1,2, A) to evoke the complete interchangeability of cinematic (or sculptural) objects and thus, as he said, »ruin their destiny«. But these destinies are extremely strongly established in classical narrative cinema, for example, so that even practising cinema sceptics like Broodthaers cannot do much against the fact. Whether, as is at times claimed, he wanted to revive a »cinema of the attractions« to counterbalance the infantile spectacle culture and thus created a blueprint for the film installations that are so popular today is an open question. What is certain is that no attraction with regard to cinematic representation and presentation seemed so strong to »Section Cinéma« for it not to be able to be countered with the appropriate means.

Of course, this functioned only within a small framework, whether transportable or temporary. Which is why the idea of a stable and definitively valid form of presentation will always remain alien to Broodthaers’ films.

Translated by Timothy Jones

The exhibition »Riss/Lücke/Scharnier« was on display in the gallery Nächst St. Stephan, Vienna, from 24 November 2006 to 10 February 2007.

Parts of Broodthaers’ cinematic oeuvre were previously shown in the exhibition »Marcel Broodthaers« (Kunsthalle Wien, July to October 2003).

The comprehensive catalogue »Marcel Broodthaers – Cinéma« (Kunsthalle Düsseldorf, Nationalgalerie im Hamburger Bahnhof Berlin, 1997) is unfortunately out of print.