Issue 2/2007 - Leben/Überleben

Re-presentation of the repressed

Art as a mirror of the social unconscious?

There are signs that a reinterpretation of the neo-avantgarde and 1950s abstract art is on the agenda and on the horizon. If we read the images, titles and testimonies of the artists with the knowledge and experience of the present, we end up with a re-reading. In the aftermath of Derrida’s deconstruction it is no longer possible to read and understand the word »trace« in the same way as in the 1950s. After Lacan’s return to Freud and Heidegger’s definition of truth as dis-covery, we can no longer read the terms symbolic, imaginary and real, or indeed hide and conceal, as used in commentaries of the era, with the same innocent and naïve gaze as back then. After Giorgio Agamben’s work, which builds on the foundations of Benjamin’s philosophy, or rather theology, of history and in particular in the wake of Foucault’s criticism of representation, it is also no longer possible to narrate the history of art as a system of representation as we did before, as if it were a continuum, without caesurae. The question thus arises of what is silenced, hidden and concealed in post-war art, from Samuel Beckett to the ZERO group. Why have the traces been wiped out, why is there so much muteness, emptiness and silence? Why is what is dis-covered simultaneously nihilated?

When we read the vocabulary of the past whilst drawing on the expertise of contemporary theories of culture, we recognise the psychoanalytical termini of repression, forgetting and defensive mechanisms in commentaries from that era. The most familiar defensive mechanisms, whereby the ego seeks to wipe out the contradictory demands of the unconscious and the id on the one hand and of the social super-ego on the other hand, include reaction formation, identification, projection, sublimation and rejection. That means there is a need to ask what is supposed to be repressed and forgotten. Apparently the truth, the experience of truth and the subject that perceives this truth are structured in such a way that the subject can no longer perceive the truth and no longer even knows who this subject is. This state is known as taboo, meaning the state of affairs in which one cannot speak about certain events and does not wish to hear about them either. The war, the Nazi regime, the Holocaust, the oppression of women, the destruction of the subject, barbarism all became taboo topics.

To that extent we now understand which traces had to be covered over, what had to be concealed and silenced and which cries were meant to be stifled.

As we know, the repressed and the taboo bubble back up to the surface, albeit in the masked mode with which the unconscious communicates with us. What is represented is not just the conscious and intended; the unconscious and unintended can be represented too. This form of representation is naturally not a realistic mirror of how the eye perceives reality, not simple mimesis, but instead takes the form of the mask, of deformation and dissimulation, straightening out and distortion, in other words, it assumes the shape of metaphors and metonymies, as in dreams.

Representation can be understood as a system of symptoms. A positive answer can thus be given to Jean Paul Sartre’s critical question concerning the unconscious, the »knowledge that does not know itself«. The unconscious can be represented, both the individual unconscious and the social unconscious. Knowledge that does not know about itself can also be represented i.e. known in the shape of dreams, symptoms and also in forms from art. Echoing Foucault, one might enquire why certain meanings are expressed in art and not in science. The answer runs as follows: society itself turns our unacceptable wishes and knowledge away from us. There is knowledge in our society that is repressed by society itself. Camouflaged as art, this social unconscious, this repressed material can find its way back into consciousness and reality.

A merely iconic comprehension of visual representation has certain limitations as an instrument, for it reduces itself more or less to a simple retinal representation. As a model of the unconscious and repressed, Freud’s »Wunderblock« (1924/1925), or »mystic writing pad«, demonstrates that reality is multi-faceted and that the mechanisms of representation do not simply represent external reality but are instead much more complex. The dynamic interaction between internal and external mechanisms of representation, which are reflected in the dynamic interactions of the conscious and the unconscious, demonstrate that the representation of reality also includes the representation of unreasonableness and irreality and that it does not suffice to define a representation solely in isomorphic terms. That is the statement made by René Magritte’s famous painting »Ceci n’est pas un pipe« (This is not a pipe, 1928/29). In a nutshell: what you see is not the whole story. That is also the reason why this work exerted such a fascination on critics of representation such as Foucault. If we opt not to move beyond the concept of a purely visual representation, then we have to deny the possibility that music and painting have a political dimension; this was Sartre’s starting point when he proclaimed in his essay »What is Literature?« (1947) that only literature, in other words a complex text, could have political dimensions and that this was not the case for disciplines such as music and painting.

In addition to Freud’s mystical writing pad, psychoanalytical theories also offer other models of representation of the repressed that serve to devise an aesthetic of symptoms. These include highly effective defensive mechanisms of sublimation, transference and reaction formation. The latter is one of the most powerful concepts when seeking to comprehend how the neo-avantgarde functions.

[b]Taboo and reaction formation[/b]

The contemporary problem of repression and representation is the problem of the taboo. When something happens that cannot be accepted, either by the individual or by an institution, in other words, by either a subject or a social system, then it is not possible to talk about it or to find out anything about it. However, as we know, the repressed will resurface one way or another. The classical formula »speculum artibus« should thus be understood in the following terms: art is a mirror of society, yet not just as an icon or symbol but also disguised as a symptom. This clash of two different systems, the representation of reality and the representation of the unconscious, can be traced most clearly in the sphere of the taboo.

The greatest taboo of modern times is the Holocaust. For the modern spirit – the Cartesian subject of the Enlightenment – it is utterly unacceptable that the Holocaust was possible at all in highly civilized Europe. After two World Wars and the Holocaust it became clear that the classical options for representation must draw to a close. Adorno in particular expressed this with great clarity in his 1949 essay »Kulturkritik und Gesellschaft« (» An Essay on Cultural Criticism and Society«):

»The critique of culture is confronted with the last stage in the dialectic of culture and barbarism: to write a poem after Auschwitz is barbaric, and that corrodes also the knowledge which expresses why it has become impossible to write poetry today. «

Raul Hilberg, an academic working on the Holocaust, made a similar statement in his book »Unerbetene Erinnerung: Der Weg eines Holocaust-Forschers« (1994) (»The Politics of Memory: The journey of a Holocaust historian«). He cannot conceive of any appropriate form of visual representation to represent Hitler’s Germany and ultimately refers to a real situation to release the repressed and allow it to return.

He proposes taking a can of Zyklon B gas, just like that used to exterminate Jews in Auschwitz and elsewhere, and setting it on a pedestal in a small and otherwise empty room as the quintessential expression of Hitler Germany. On one occasion a vase by Euphronius – embodying the quintessence of Greek Antiquity – was presented in the Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art in a similar manner.

I propose that we should draw on the psychoanalytical model of representation of the unconscious to understand what art really reflects. In the first phase of modern art, artists such as Pablo Picasso or Francis Bacon strove to show images of deformed bodies – a deformation of reality. From Picasso to Bacon art was still following the classical logic of visual representation. A destroyed city such as Guernica is portrayed by a destroyed representation. However, decades before »Guernica« was painted, Cubism had already destroyed perspective as a mode of representation. Picasso’s destruction of classical representation has nothing to do with the devastated city of Guernica. Actually, audiences love this painting merely as a consequence of a misunderstanding – for the formal destruction of the representational system and the destruction of the city happen by chance to coincide. The style and subject-matter fit together – by coincidence. One could say that the destroyed faces in works by Picasso or Bacon reflect the destruction of human values in the two world wars.

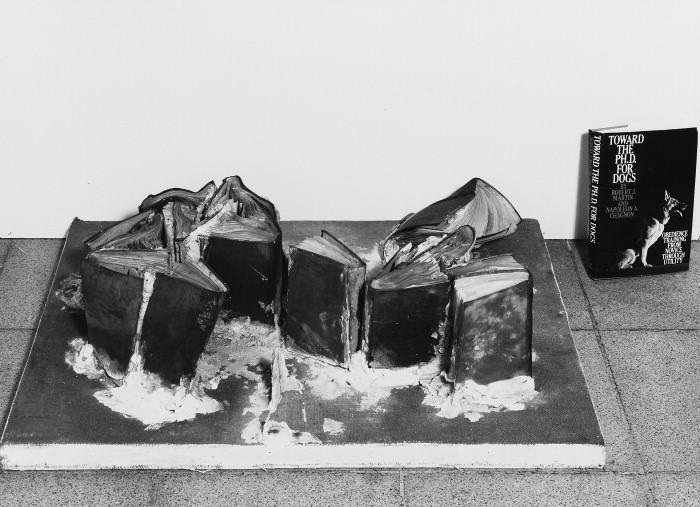

The real crisis of representation emerged during the post-war advent of the neo-avantgarde when it was not just the system of representation that was destroyed but also the »tools« of representation. From Arnulf Rainer to Lucio Fontana, from Gutaj to Gustav Metzger, we see destroyed canvases; from the Wiener Gruppe through to Fluxus destroyed musical instruments crop up; from happenings to John Latham we find destroyed books, canvases and films.

The case of Yves Klein serves to illustrate the limitations of a formal interpretation of this type of art. The reason for Yves Klein’s rejection of representation, the way he destroyed canvases with fire and celebrated traces of bodies on canvases was the traumatic experience of Hiroshima, when the nuclear bomb was dropped. He was thus in a certain sense a pupil of Adorno and Hilberg. When he was young Klein had visited Japan, seen the traces of the victims and realised that he could no longer represent the horror of nuclear war visually in a classical mimetic manner by deforming the visual system of representation as Picasso had done. Just like the heroes of the theatre of the absurd and other representative of the neo-avantgarde, after 1945 Klein found it extremely difficult to believe in traditional culture, for that culture had not prevented the horrific scenario. Even worse; this horror was committed in the name of culture. For this reason Klein, like a number of others, decided to destroy not only the mechanisms of representation but also the means of representation, the tools, the dispositives, in order to reveal the horrors of nuclear war.

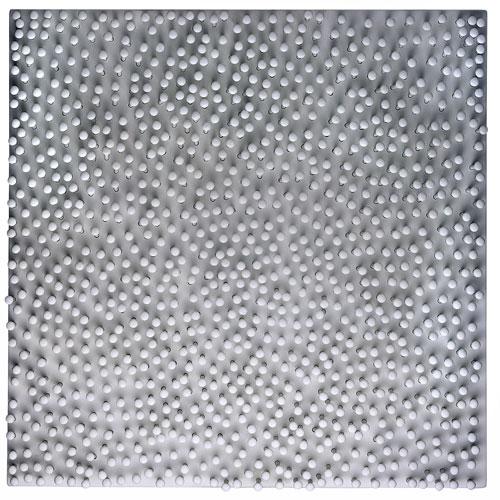

The ZERO group and many others, such as Fontana, Manzoni etc. also engaged in the practice of destroying the means of representation. Reception of this group of artists after the Second World War reveals a misunderstanding. After the war people did not want to hear anything about the conflict, let alone talk about it. The war became a taboo. People saw their own obliterated memories in the blanked-out white canvases of the ZERO group. That is why they liked the gesture of effacement in art, from Rainer to Rauschenberg, because their memories, their involvement with fascism, were rubbed out (Fontana may even have had very personal reasons – he had worked for Mussolini, producing fascist sculptures).

Shooting at canvases as Nikki de Saint-Phalle did or bombarding them with arrows, like Uecker around 1960, or with acid like Gustav Metzger, John Latham’s book-burning – all these actions reveal a profound mistrust of the tools of art, the means of cultural memory and culture itself. Along with many other similar art actions, the 1966 »Destruction in Art Symposium (DIAS)« in London and happenings by Franz Kaltenbeck and Peter Weibel, who secretly smashed museum windows at night in 1968, demonstrate the insurgencies that were unfolding on the plane of the means of representation.

Viennese Actionism with its rituals and self-mutilations, real or simulated, the dirtying and contamination, the spraying around of paint or filth, dirt, urine and faeces are clearly unconscious reaction formations as »defilement« (Nitsch), expressed in art, against the conscious »cleansing« of post-war Austria from its crimes in the Second World War and its involvement in fascism and the Holocaust. After 1945 Austria officially denied having been part of German National Socialism and portrayed itself as a victim of National Socialism. This famous »victim lie« formed the basis for the establishment of the Second Austrian Republic. As Austria was cleansing itself »officially« and »thoroughly«, art did the exact opposite. It wallowed in impurity, blood and dirt. Representational mechanisms in art do not represent only what one sees and knows on a conscious level but also what one does not see and what one represses. A true representation, a true image can only be created by exploring reaction formation and other similar defensive mechanisms in society and individuals.

Of course, reaction formation is itself an unconscious response of art, not a conscious move to shed light on events. One might address this reproach to Actionism. There is a danger that reaction formation becomes part of repression or indeed even an accomplice of this process. Yet art as a symptom is nonetheless a truth, even if merely a disguised verity.

Re-representation, or more precisely: the return of the repressed trauma of the two World Wars, the Holocaust and the dropping of the nuclear bomb comprise the content of the neo-avantgarde. The neo-avantgarde is not a purely formal repetition of the historical avantgarde. It is genuine post-war art, art about memory, forgetting, repression, trauma and the return of the repressed. In this role, the neo-avantgarde begins to critically explore the transformation of the dreadful experience of the Second World War up until the Year Zero of a grey pseudo-democracy.

Translated by Helen Ferguson