»Finally,« a friend commented with relief while we were looking at Google+ last July, »it was so annoying having one thousand Facebook friends, all mixed up with no differentiation. Now you can divide them into groups and the information will be filtered accordingly. Very practical…«. Maybe, I thought, but will Google’s + practical circles limit the increasing score of Facebook friends? Will our mentality towards online friending change? Or are the circles proposing yet another rating for our networked connections? In any case, the idea of a friends’ hierarchy is not new. Facebook had initiated the Top 8 Friends list back in 2007 and MySpace even earlier. Yet, with Google+, the call for a differentiation of one’s contacts was more apparent, possibly because it was taken as a response to Facebook’s thousands of friends mess. Google+ again confronted us with an old school-like problem: who are our real friends and how many are they? It probably felt a bit weird and uncomfortable deciding on the circles of our contacts. But we responded to it, like we always do. After all, »today\'s multitude has something childish in it: but this something is as serious as can be«, as Paolo Virno has written (Virno, 2004). We repeat mentalities and actions like children do in order to find new »common spaces« where we can feel at home. Platforms like Google seem to know how to take this into consideration every time they create a new interaction and participation context. And they also make it very easy for us: We only need to jump in, contribute and connect to our friends. We are being treated like kids and amateurs at the same time but we do not care. We respond every time with the same curiosity and excitement. But, what drives this interest of ours? Which mechanisms are being used by the platforms to encourage our participation and engagement, for which purpose and what outcomes do they bring? This article will aim to critically discuss the creation, support and maintaining of today’s social relationships and friendships under the influence of a new emerging theory, called gamification.

[b]Towards new gamespaces[/b]

The social media world is a competitive world. Friends’ or followers’ scores, likes’ ratings and comments’ counts are some of the most common features in a social network profile. Numbers matter. Not only because they offer a certain sense of self affirmation to the user but also because they define what to see and what to pay attention to. Numbers reveal how social we are, how popular our sayings are, how interesting our everyday life appears to be. Either we realize it or not, in the era of attention economy, our success is being estimated by numbers of friends, uploads, likes and posts. Our activities and thoughts are being announced on newsfeed boards as if they were movements of players in a game. We follow this board every time we log in and we are being triggered by it. We feel rewarded when we see on it a discussion of a great number of comments following a post of ours or a photo from our summer holidays that tens of people have liked. Scores, news boards and status announcements form the new terrain of our everyday online interaction which looks more and more like a gamespace. There are rules that we need to follow and there are constraints that we shall accept over our identity, privacy and ownership. And we do. Because we are given the opportunity to belong to a community and to feel that we stand out of it at the same time. The micro reality of the social media offers a game territory where there is not really any chance to lose. The only compromise we need to make is that we are always playing on somebody else’s ground.

[b]The challenge of gamification[/b]

The social media are simply being gamified, Gabe Zicherman, one of gamification’s supporters would say as a response to the above (Zicherman 2010). The process which reflects the integration of game elements into non-game activities and contexts in order to affect human behavior, is being discussed more and more nowadays. Health, education, work, advertising and the web world are some of the areas where gamification finds a fruitful ground. Gamification is therefore not about games but about turning everyday life aspects into gamespaces and about encouraging the participants who could be patients, students, workers customers or users etc to act as players within this very environment. People get motivated and highly engaged in activities when the process is pleasurable and interesting. For this reason, according to the supporters of this new trend, the application of game mechanics and game dynamics is required which basically means points, levels, leaderboards on one hand and awards, affirmations and achievement on the other.

One of gamification’s greatest believers, Jane McGonigal, argues that society itself can be restructured in better ways through such processes. Paying special attention to the emotional activation that only games can bring, she writes that she sees a future in which games will »satisfy our hunger to be challenged and rewarded, to be creative and successful, to be social and part of something larger than ourselves … Games build stronger social bonds and lead to more active social networks. The more time we spend interacting within our social networks, the more likely we are to generate a subset of positive emotions…« (McGonigal 2011). McGonigal’s thoughts are surely filled with positivism and if we believe in them, we can hope for better, more substantial and long lasting relationships and friendships. In her book, among other issues, she discusses how game environments can help us express admiration and sympathy, how we learn to overcome embarrassment and to feel proud also for the achievements of others. But if this is so, if game like activities encourage positive emotions and build strong ties within networks, then we should be able to observe the first encouraging signs already. So, how do we feel towards our 1000 plus friends? Did the metrics, the competition, the rules and the constraints applied to our relationships allow room for the positive emotions McGonigal refers to? Or simply, where did it go wrong with our online friends?

[b]Processing friends[/b]

On the other side of McGonigal’s optimism, we can find Sherry Turkle’s skeptical thought and Danah Boyd’s exploratory eye. Without being a luddite, Turkle aims to explain how we got to be »alone together«. Based on interviews she has conducted, she describes how the mediation of technology affects us and how we have come to a point that we process, pause or next one another just like we do with the information we access online (Turkle 2011). Moves are quick, in asynchronous or real time. We are used to be contacted, to be friended, to be liked, to be tagged but we know that unliking, untagging and unfriending is also possible. When people are processed, relationships are processed too. And sometimes the absence, the undo move is not even noticed, simply because the game has too many players inside. At the same time having many friends is important, not only for our online social status, but primarily for the justification of our online presence itself. Danah Boyd in her research regarding friendship within social networks argues that »while Friending is a social act, the actual collection of Friends and the display of Top Friends provides space for people to engage in identity performance«. Our friends therefore become our audience, the people we will address to, waiting for their actions to complement ours. We make a move only to expect the next one from them. Friends are our context; we need them to perform our identity as we build our communities in very egocentric ways, she writes (Boyd 2006).

[b]Capitalising friends[/b]

Our friends have value in the networked reality. Their gamification unavoidably leads to different levels of their commodification and expropriation. To realize this, we only need to be reminded of the different ‘categories’ of online friendship which generally are: our real friends, our friends of friends and a wider network of people to whom we have connected because we admire them or respect them. This third category of ‘high quality’ friends plays an interesting role in the capitalization of friendship. They are the ones users connect to in order to not only upgrade their social status– a classic society cliché- but also to get higher chances for job opportunities. As companies tend to check more and more the social media profiles of their potential employees, it is expected that the ones with expanded networks of ‘high quality’ friends will be preferred (Andrejevic 2011). The quality and quantity of friends become therefore the metrics of power for the new social capital which is being aggregated. And the main aggregators are of course the big social networking sites themselves, which actually fight over ownership of our friends. Last summer Facebook did not allow the export of friends to Google+. We were not allowed to ‘move’ them with us. Our friends are not our friends like our data is not our data. They are part of the wealth we create as prosumers of the new networked society of the post-Fordist condition. It is our potential and disposal that builds the social relationships and accordingly the social capital. But its liberation from the market is still a crucial request.

[b]Loving the same[/b]

Our online friendships are based on sameness. The networks keep reminding us how many friends, photos or videos we have in common while we keep looking for things to ‘like’ and to ‘share’. As Richard Rogers writes in his introduction for the post-demographics, of interest today are not the traditional demographics of race, ethnicity, age, income, and educational level – or derivations thereof such as class – but rather the demographics of tastes, interests, favorites, groups, accepted invitations, installed apps and other information that comprises an online profile and its accompanying baggage (Rogers 2009). This is what the networks encourage and this is what the market can be fed with. The circle is vicious. The more posts and likes we do, the more suggestions the market will have for us through our friends. The so called diversity, polyphony, heterogeneity of the internet is fading while we are we reproducing tastes and prejudices of each other. Are we allowed to see further and open up for new friends beyond the recommended and the expected?

[b]Opposing gamification[/b]

Gamification’s connection to the market is an undoubted fact. There might be some idealists who think that really games can change the world, but reality shows that gamification is a strategy of capitalism and its honest aim is to engage people in certain behaviours that connect to services or products. While Gamification still has a long way to go to show that it is an efficient market strategy, it is important to mention that right from the start it met many opponents for the impact it can have on the social relations and for the management it aims to succeed. Playful tactics and practices were developed by users, creators, programmers and researchers in order to break the rules of the new game layer that was being imposed.

A very interesting example can be found in the history of Friendster, as mentioned by Danah Boyd. It is the story of the Fakesters, the fake profiles that were created by the users in order to cheat the platform in its glorious days. Friendster did not allow its users to browse profiles that exceeded four degrees of separation (friends of friends of friends of friends). The Fakesters came as a response to this. They were profiles invented by the users for actors, popstars, ideas, songs to which a lot of people could connect and use them as hubs to get more access. Of course the accounts were at some point terminated by Friendster, but it is true that a hole was created in the system and it was done successfully and on a collective basis.

In the case of Facebook, users right from the start have been playing with tagging and linking, creating small acts of sabotage that were confusing the system. Irrational, humorous, weird ideas and actions are created as fun pages which succeed in breaking the productivity chain as no sense can be made for the market. Sean Dockray in his Suicide Facebook (Bomb) Manifesto writes that if we really want to fight the system we should drown it in data, we should »catch as many viruses as possible; click on as many \"Like\" buttons as possible; join as many groups as possible; request as many friends as possible. Wherever there is the possibility for action, take it, and take it without any thought whatsoever. Become a machine for clicking!« We should aim to become »everything instead of nothing« in the system. (Dockray 2010)

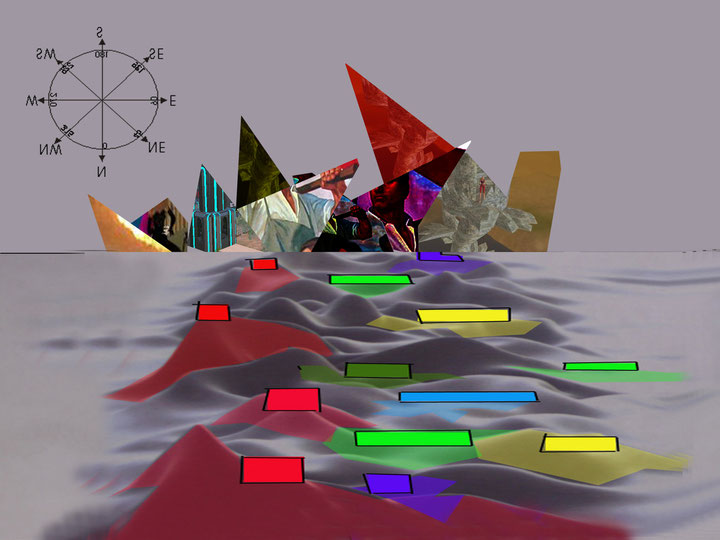

Dockray’s manifesto followed the »web 2.0 Suicide Machine« by the Moddr team and the »Sepukoo« of les Liens Invisibles, two projects that accidentally developed a similar software at the same time in 2009 which enable users to commit suicide , to delete a users account permanently, something that was not allowed from most social networks. Dockray proposes (over)presence to the absence that this type of software suggested, but one needs to admit that both »Sepukoo« and the »web 2.0 Suicide Machine« are projects that succeeded with their irony and playfulness to attract the attention of the users and raise awareness for the constraints of the social networks over our relationships and our data. Using the mechanism of the game, they created a parody of the mechanisms of the social networking sites, presenting elements such as top suiciders lists. Another project which goes towards this direction and actually builds a game metaphor for the social media is the Folded In by the Personal Cinema collective. Based on the YouTube video wars, Folded In highlighted the game mechanics used in the popular video platform and the ways users engage with them. While navigating and playing in the space, one can realize the impact counts, ratings, tag clouds and comments have in a competitive and highly populated network such as YouTube.

An interesting number of other projects which examine the mechanisms of the networks and their impact on social relationships can also be mentioned. Such as the »Add to friends« by Nicolas Frespech where the user adds to an excessive number of friends of the artist, the »elfriendo« service by Govcom.org that generates myspace user profiles along with compatibility tests and taste construction, or the MyFrienemies by Angie Waller and the Hatebook by Nils Andres that reversed the hierarchy of friendship to a hierarchy of hate and a policy of likes to a policy of dislikes.

[b]Final thoughts[/b]

Gamification is a ‘parody of itself’, a ‘feedback loop’ Dacota Reese Brown, a game designer argues. It is like a ludic flavor that is not really needed and can not really bring changes to human behaviour. It can only reinforce the existing tendencies for the profit of the market (Brown 2011). And so it happened in the case of friendship. Since kids we always wanted to be popular and we were competitive with and for our friends. But on the other hand, we never felt that we needed rewards in order to make friends. We never really needed intermediaries and external incentives for our social relationships. The ‘walled gardens’ where our friendships are growing today are not only making profit out of our friending traffic; they also slowly change our very perception of friendship. Indicators of sameness and likeness take the leading role as we turn more and more towards the taste of our friends and not the friends themselves. A corrupted form of friendship might be growing within the gamified social web. As Hardt and Negri have written, we are still possessed by the love of the same, and the love of becoming the same, instead of appreciating the ‘otherness’ of a friend, which lies beyond any market and opens the way for a new common ground (Hardt & Negri 2009).

In his beautifully written piece »The friend« Giorgio Agamben writes that friendship is a proximity that resists representation and conceptualization. It is not a property, it is existential and not caterigocal. Referring to Aristotle he puts the emphasis on the con-division, on the act of sharing, of sharing not some object but life itself (Agamben 2009). It is the experience of friendship that the friends share, the philosopher says. This is possibly the element where we can start again, to create a form of sharing that can not be gamified, commodified or become the object of control.

References

Giorgio Agamben, »The friend« in What is an apparatus, California: Stanford University Press, 2009

Mark Andrejevic, »Social Networking Exploitation« in A Networked Self: Identity, Community, and Culture on Social Network Sites, ed. Zizi Papacharissi, New York: Routledge, 2011

Danah Boyd, »Friends, Friendsters and Top 8: Writing community into being on social networking sites« in First Monday (2006), last accessed 10.08.2011

Dakota Reese Brown, »The current and Unfortunate State of Gamification« in How Stuff Works, http://www.howstuffworks.com/framed.htm?parent=gamification.htm&url=http://dakotareese.com/2011/01/the-current-and-unfortunate-state-of-gamification/

Last accessed 10.08.2011

Sean Dockray, »Facebook Suicide (Bomb) Manifesto« in http://spd.e-rat.org/writing/facebook-suicide-bomb-manifesto.html, (2010) last accessed 10.08.2011

Michael Hardt & Antonio Negri, Common Wealth, Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009

Jane McGonigal, Reality is Broken, Why games make us better and how they can change the world, London: The Penguin Press, 2011

Richard Rogers, »Post-demographic Machines« in Walled Gardens ed. Annet Dekker & Annette Wolfsberger, Eidhoven: Lecturis, 2009

Sherry Turkle, Alone Together, Why we expect more from technology and less from each other, New York: Basic Books, 2011

Paolo Virno, The Grammar of the Multitude, Trans. Isabella Bertoletti

James Cascaito, Andrea Casson (Los Angeles/ New York : Semiotext(e), 2004)

Gabe Zichermann, »How To Make Facebook, FedEx, And Amazon More Fun« in http://techcrunch.com/2010/03/27/facebook-fedex-amazon-fun/ , last accessed 10.08.2011

This research has been co-financed by the European Union (European Social Fund – ESF) and Greek national funds through the Operational Program \"Education and Lifelong Learning\" of the National Strategic Reference Framework (NSRF) - Research Funding Program: Heracleitus II. Investing in knowledge society through the European Social Fund.