The nationalist tendencies which dominated Moldovan society at the beginning of the '90s and were based on the rewriting of history; radical changes at the level of the city identity; demolishing Soviet monuments and building new ones; and renaming streets and boulevards in accordance with the spirit of the “new” times, have caused a substantial reconfiguration of public space in Chisinau. As a result an important section of public properties designed and built mainly during the socialist period, including historic buildings, industrial zones, green areas, squares, parks and other public spaces have been taken over through the practice of privatization imposed by the new economic logic.

Actually as the authorities of Chisinau were preoccupied by the reconfiguration of public space at a symbolic level, they completely neglected the historic architectural patrimony of the city. The city leaders that succeeded weren’t concerned about the value of the city centre or about creating a solid base for an efficient protection of public propriety and the historic patrimony of the city. The plan for modernizing the core center of Chisinau, elaborated by a project team led by Alexei Shchiusev after World War Two, remained permanently on the agenda of local authorities. It was reconsidered many times, and viewed constantly as one of the key elements in the development of the city. Even after the reconstruction of the city, Chisinau was considered to be a locality with the largest number of preserved historic buildings.

The status of the historic city of Chisinau was reconfirmed in 1993, when by the Decision of Parliament (No. 1531-XII, 22nd of June, 1993) the city centre, together with a large number of 19th and 20th century buildings, was declared a historic and architectural monument of national importance, thus included in the Register of Monuments of the Republic of Moldova and therefore protected by the state. Nevertheless, no municipal structures for protecting, restoring and valuing the architectural patrimony of the capital have been created.

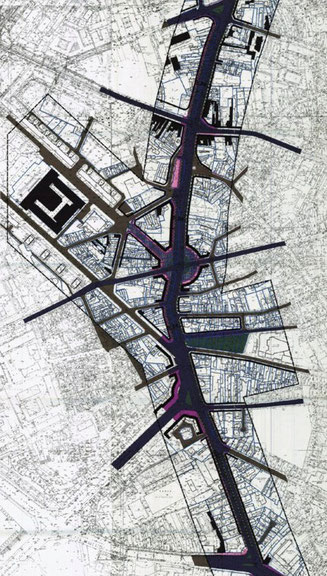

The overall context in which the city developed after 1992 may be interpreted as if things have been intentionally left to degrade, in order to force the people to move elsewhere and to build here a different urban structure, to produce modernization by negating the historically built heritage. Following this policy of negligence the city residents woke up in a mutilated city, with dispossessed public spaces, into a disfigured and hyper populated historic centre because of the constructions placed in the very core of the old city, and the culmination of this irresponsible strategy of city management will be the construction of Cantemir Boulevard, planned – according to the Master Plan (PUG) and Zonal Plan (PUZ) – to pass directly through the historic city centre.

Modernization strategies imposed in Yerevan and Bucharest

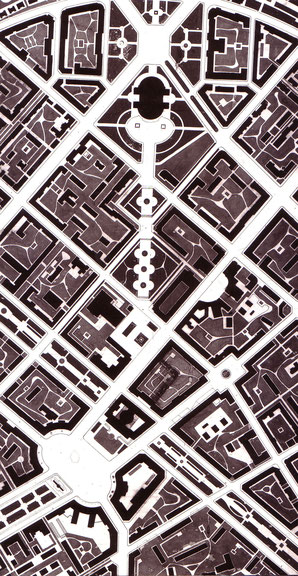

In this context it is useful to mention several examples (case studies) of radical approaches to urban planning and development, which can be followed in the context of post-Socialist countries and which denotes a set of similar practices by the way they are implemented. The similarities are related not only to the logic of neoliberalism , but also to the fact that they recycle outdated plans for development (elaborated 30 – 40 years ago), such as the Cantemir Boulevard in Chisinau, the pedestrian boulevard, Northern Avenue in Yerevan, and the construction of Buzesti – Berzei Axis in Bucharest, also known as Buzesti-Berzei-Uranus Boulevard.

The enlargement of the boulevard by building the Buzesti – Berzei Axis in Bucharest is a recent example of applying these types of urban policies. It’s a project in progress with grave consequences on the old area of the city, which has been monitored and contested by civil society in Romania. However, the idea for this type of city development is rooted in an urban plan from 1935, when a new boulevard was conceived following a similar path.

A marker highlighting the destructive treatment applied to the city is the building in Haralambie Botescu Square No. 18, part of the ensemble type historic monument Calea Griviței. The house was built at the end of the 19th century in an eclectic style with decorative elements of Ottoman-Oriental influence. The details of the Zonal Plan (PUZ) of the Protected Construction Zone No. 2 – Calea Griviței, approved by HCGMB No.34/2009, provided “obligatory conservation” for this building. The Detailed Plan approved by HCGMB 132/2013 for this segment of the Buzesti – Berzei Axis regulated for the preservation of an important part of the building and reorienting of the central façade. This should have been done by 16 degrees, according to declarations from the project designer of the Zonal Plan (PUZ) from 2011. Later, due to lack of time and resources the building was demolished overnight, and the conditions imposed by the project have not been respected. In general, the solution seems to violate and ignore any operations that would provide some minimal effort in order to preserve the architectural patrimony.

We can find a comparable example today, the Northern Avenue recently built in Yerevan and inaugurated by the local authorities with grandiose ceremony in 2007. Designed by the main architect of the city, Alexander Tamanian in 1924, it was not implemented during the Soviet period. A decade after the disintegration of the Soviet Union, the City Council of Yerevan decided to proceed with its construction, which began in 2002, based on Alexander Tamanian’s initial plan, but developed and redesigned by architect Jim Torosyan. According to the initial plan, the National Gallery and the History Museum in Republic Square, have not been planned to be built on the present location, so that the boulevard ends near these buildings, without having an opening towards the Republic Square, therefore it has no finality and no opening which would allow the flow of pedestrian traffic.

In order to have an impression of the scale of this project, we note that the Boulevard consists mainly of commercial spaces and luxury apartments with a total surface of 320,000 square meters, and also includes underground garages for 2000 cars. Into this 27 meter wide pedestrian boulevard, has been invested 101 billion drams (more than $330 million dollars), and at the official inauguration of the boulevard, on 16th of November 2007, president Robert Kocharyan mentioned that the Republic Square and Northern Avenue represent the “business cards” of Yerevan.

Let us reflect on what are the real consequences and costs of this project. The construction of the Northern Avenue was financed by the private sector. The mechanism functioned as follows: the government purchased all small properties along the route where the boulevard was to be constructed, consolidating these lots into larger sections, in order to create favourable conditions for developers and property investments, after which the government auctioned them off to the highest bidders.

This process has been conducted section by section, which provoked waves of protests from the owners of the properties purchased abusively. Finally, after adopting an arbitrary law in 2001, (later named “state needs, both the Armenian Constitution and the first protocol from Article 1 of the European Convention on Human Rights have been infringed upon, leading to the redistribution of properties. As a result of this decision taken by the government of Armenia, over 40 citizens of the state have been dispossessed under the pretext of “state needs”, these people have not only been left homeless, but have also lost even their certificate of residence, therefore losing some of their constitutional rights as citizens.

Analysing the impact of these policies we may ask ourselves, what is the logic behind these wider machinations? For whose benefit are these boulevards built, with unrecoverable interventions at the level of urban texture? These interventions provoke the destruction of both the urban and social fabric, and cause grave consequences as those that have already taken place in Yerevan, Bucharest and most certainly will take place in Chisinau?

Dimitrie Cantemir Boulevard – an instrument of gentrification at the heart of the city

The adoption of the Master Plan of Chisinau in 2007 represents in our view a culmination of neoliberal vision with negative consequences upon the architectural patrimony in the historic city centre. The solutions promoted by the new Master Plan include: cutting directly through the historic centre of Dimitrie Cantemir Boulevard, enlargement of a section which will occasionally imply demolition and in some cases considerable enlargement of other streets, etc., all this involving the modification of the old street structure and the demolition of an important part of 19th and 20th century city heritage.

The construction of Dimitrie Cantemir Boulevard was initiated as early as the '80s, to be continued in the following decades, but because of the economic, social and finally political changes at the end of the '80s they have not been possible. Actually the Cantemir Boulevard Project is anchored in recent history and represents a reminiscence of the Master Plan developed under the leadership of Alexei Shchiusev. Through that vast project (elaborated between 1945 – 1947) it was intended that the “lower” zone of the city be synchronised with the “higher” zone of Chisinau, from the 19th century. Now we can only be dismayed that the older part of the city was not perceived as a historic monument, or given a certain value. At the time it was considered that its value can be neglected and therefore it can be demolished without hesitation, and because Shchiusev’s name had importance, this idea passed from project to project and has been followed like an axiom, without question or reflection. According to the present Master Plan, Dimitrie Cantemir Boulevard could be constructed to reach Cosmonauts street, as far as the surroundings of the National Bank, and according to the initial project from 1972 the boulevard (now Cantemir) was supposed to be enlarged as far as Calea Iesilor street.

Going over these plans, we can affirm with certainty that the construction of the Dimitrie Cantemir axis involves the loss of buildings which are important for the identity of the city and this will make the area more fragile. In addition, there are arguments that, once built, the road will not even resolve the traffic problem. Actually, the break would stimulate the circulation in this portion of the city, bearing in mind that Chisinau is pierced in its lower part by several boulevards of this kind. Following public debates on the Master Plan, critics have expressed the opinion that the encouragement to traverse the city through the “lower” zone of the city is unjustified, as this will lead to its over agglomeration. On the contrary, the circulation of traffic through inner and outer surrounding roads should be encouraged.

After the unsuccessful experiences of the '60s and '70s, Western cities have renounced strategies to break and enlarge their urban roads. Cities across Europe and the USA no longer conduct works for car infrastructure in their central zones, because of the negative effects generated by these through excessive pollution, segregation of public space, and especially traffic congestion.

Proposing an Alternative Conclusion

A new paradigm must be introduced into the local administration’s perception and disrupt the neo-liberal logic through which it is intended to manage the city and its theoretically protected historical centre. A new approach that implies the removal of traffic from the “lower” part of the city, along with an investment in protecting the architectural patrimony and conservation of the historic centre of the city.

Actually there would be some efficient solutions for solving the transport problem, such as to renounce the idea of building Dimitrie Cantemir Bd (modifying or replacing the idea of the boulevard with a different project based on non-destructive principles), withdrawal of the objectives which attract private and public transport into the central area – large stores, the central market, many offices, the intercity bus station, and which must find their place on the periphery of the city.

The opinion of local architects and urbanists who are opposed to the project, is that the most effective solution for the increase in traffic flow would be to move or direct the traffic towards Albisoara street, This can be widened without demolition or major investment, and by transforming it into a street of municipal importance, would allow the redirection of traffic by avoiding the city centre. Another fundamental measure at this moment would be to elaborate a new approach regarding the rehabilitation of the historic zone of the city, with an emphasis on maintaining the integrity of the downtown part of the city based on preserving the social fabric and protecting the existing urban environment. The format of a public/private partnership may be another solution that would allow the city administration to elaborate and implement an alternative project to Cantemir Boulevard. We have the impression that these and other possible solutions are not being sufficiently explored by the city administration, in meaningful ways which could overcome the blocking at the level of ideas.

A possible impetus that could affect the city authorities with a determination to adopt a new strategy rests in the hands of a group of civic initiatives, such as: “My Dear City” association, “Save My Green Chisinau” initiative, “Postmen of Chisinau” movement, along with other civic groups and associations which have coalesced within the recent period. These groups are concerned with signalling abuses, deficiencies, deviations, and in some cases demolitions of buildings of major importance (a notorious example being the demolition of the Post Office building on Vlaicu Parcalab Street) approved by the municipal administration, along with infringement of legislation and direct abuses in city administration. There are hopes that these civic initiatives could form a solid coalition, a lever through which the makers of urban policies would be brought to respect the law on protecting the architectural patrimony of the city, making this an imperative that can no longer be ignored.

The Ghost Boulevard of Chisinau

A ghost boulevard is haunting the city and it is difficult to anticipate whether it will be built, as happened in Yerevan and Bucharest, or not. What we can certainly observe is that some buildings have already popped-up along the red lines delimited by the planned boulevard in the Master Plan, and these are clear signs that in fact the boulevard is slowly materializing. Following the fast tempo in which malls are built for current consumption and the residential blocks – investments that bring profit, we can affirm that the city has many chances to become a dormitory-city with a 19th – 20th century centre which gradually transforms into an extended commercial complex and practically returns to its initial form of a provincial fair.

It is clear that Dimitrie Cantemir boulevard is not a real necessity for the inhabitants and will affect severely the core of the city centre on many levels. The question is what shall we do to stop it?

Chisinau, 2017