Issue 3/2013 - Apparate Maschinen

Writing machines in the vineyard of the text

A conversation with Mathieu Copeland and Kenneth Goldsmith on conceptual poetry, writing the exhibition and the future of writing

“Sometime in the near future it may be necessary for the writer to be an artist as well as for the artist to be a writer”, wrote Lucy Lippard in 1968 in her essay The Dematerialization of Art.1 Today, 45 years later, both fields seem to have merged, and artists are also curators, critics and mediators of their work. Kenneth Goldsmith (52), Professor at the University of Pennsylvania, a highly respected proponent of conceptual writing and founder of UbuWeb, an online database of avant-garde films, videos and texts, thinks that is normal: “There is virtually no critical discourse on innovative poetry, which means that poets must conduct the debate themselves”. The do-it-yourself solution dovetails with Lippard’s forecast that “the contemporary critic may have to choose between a creative originality and explanatory historicism” 2. In books such as Uncreative Writing: Managing Language in a Digital Age (2011) or Against Expression: An Anthology of Conceptual Writing (2011) Goldsmith opposes the creativity postulate of art. Books like Soliloquy (2001), recording everything that he said in the course of a week or Day (2003), a handwritten transcription of an edition of the New York Times, are, in his view, conceptual art: “The idea is more important for production of the text than the text produced as a result. That is also why people discuss my books more often than actually reading them”.

As a curator Mathieu Copeland (36) also aims to trigger debate rather than to merely show exhibits: as he explains on his website, he does this by discussing “poetics of interstitial, neutral and otherwise overlooked off-spaces—and off-times—of museums and galleries”. His focus is on poetics as the functional principles underpinning presentation of artistic work. In Eine choreographierte Ausstellung (Kunsthalle St. Gallen, 2007), three members of the Stadttheater St. Gallen Dance Company translated works by Jennifer Lacy or Roman Ondák into movement. In nine empty rooms, Voids (Centre Pompidou Paris, 2009) displayed historic exhibitions of empty spaces, for example by Yves Klein or Maria Eichhorn, by simply leaving the rooms empty – and quite explicitly not reconstructing these shows, in contrast to the angle currently adopted in Germano Celant’s remake of When Attitudes Become Form, while une exposition parlée (Jeu de Paume Paris, 2013) comprised artists such as Vito Acconci or Gustav Metzger narrating stories about various artworks.

This underscoring of the performative quality of text and exhibition dovetailed with the figures involved: both Copeland and Goldsmith are charismatic individuals and enjoy public appearances in their author roles; in 2011 Goldsmith read to an audience including President Obama during A Celebration of American Poetry in the White House and, with his full beard and Paisley-patterned suit, clearly revelled in his status as an avant-garde maverick. These new conceptual approaches are apparently not concerned with a revival of a particular art movement, but rather with the “immaterial” aspect that determines the value and meaning of the works: gestures, framing conditions, words, objects. A new historical materialism, which has become necessary in the light of the audience’s enduring alienation from the materials of spectacle produced by the cultural industry. An interview with Copeland and Goldsmith conducted by email aims to highlight the critical competence this approach allows.

I asked Goldsmith what led him as an artist to move into the realm of literature in 1990. This was his reply: “In the history of the fine arts, experimental movements were generally rewarded. In fact, since the advent of the modern art world, the avant-garde has become mainstream. That is very different when it comes to writing, where there were actually two distinct strands: the mainstream and the avant-garde. The mainstream always received a great deal of support and was very popular, whereas the avant-garde was left out in the cold. The mainstream stagnated on the aesthetic front for an entire century, which explains its popularity and its intellectual impoverishment. In 1959 the poet Brion Gysin stated that literature was lagging 50 years behind painting. I would simply double that figure today. In literature, it is still possible to do things that excite people – there are a whole host of ideas that have been taken on board from the fine arts, without even ever scratching the surface of what writing is about. By deploying this kind of strategy now in writing, we can move the writerly discourse ahead, making it contemporary and meaningful. That has a lot to do with digital environments, all based on alphanumeric code (just think of the days when a JPEG was sent by e-mail and arrived as code, not as an image). It is the same material from which Shakespeare forged his sonnets, only not in the same sequence. All contemporary media – film, sound, photos – is made up of kilometre-long alphanumeric codes. That makes it crystal clear: this is a great moment for writing.”

Of course, Shakespeare did not forge his sonnets from the same material that is used to make texts today. His writing, composed with ink and a plume, is far removed from the code that makes it visible nowadays. Goldsmith’s historic bold lateral move makes clear that he is referring to text, in the sense of chains of meaning detached from writing-as-object. The separation of writing and text as material pre-dates the invention of letterpress printing. Ivan Illich sets the date around 300 years earlier.3 With the advent of silent, “inner” reading, the manuscript’s physical presence was translated into mental representation of the text. Detached from the corpus, writing became text, a tissue of imagination and presentation that can assume various forms. Since then, writing as an object has always taken centre-stage when media developments foster the impression that content is becoming dematerialised. Sound poetry and graphic poetry from the early 20th century, such as Duchamp’s instruction to copy all the abstract terms from the Larousse Dictionary and replace them with new signs, coincide with the spread of acoustic recording devices. The current awareness of the object-based character of language responds to the metamorphosis of writing from an analogue to a digital sign – reduced to a code, text becomes material, and can assume all the potential forms imaginable. What exactly does Goldsmith describe as material? “In our cultural discourse we tend to use language in much too narrow a sense, as a transparent utilisation aiming only at serving communication, more or less the way I am writing now. That is the discourse of the logos: the business world, laws, and the patriarchy. It strikes me that fictional writing has long abandoned experiments with the forms of language; that was left to poets. As a result, poetry assumes a significant role in contemporary language use.”

As Goldsmith has pointed out in another interview, this turn to using language as data material contradicts the idea that “there is no longer any need to read conceptual poetry”. Is conceptual writing concerned only with remembrance of writing, or with the gesture of writing? Goldsmith says: “Conceptual writing is involved in reprising what has already been written, and seeks to give used or worn-out texts a new lease of life. Through this act of recycling, it creates a new repository of memory, yet does so only to fling the texts once more into the morass of circulating (and cyclical) language, which emphasises their instability. Conceptual writing sets utilisation above meaning”. Utilising texts rather than finding meaning, a repository of memory, which issues language as a circulating currency – Goldsmith makes no secret of the symbolic estrangement of object and work, which he transposes into digital code. His writing draws on this, following the shift from text to context that is currently afoot in multichannel publishing, i.e. in publishing on various electronic platforms. That produces a more level playing field in terms of the conditions under which a text appears; the book loses its identity, the text loses its surrounding context. How does conceptual writing respond to that?

“I would even go so far as to say that content is no longer fundamentally important”, Goldsmith replies. “Instead it is increasingly being sidelined by the processes of its preparation and dissemination. The emphasis is not on what we shape, but rather on how we shape it. In an era in which all kinds of content are available, it becomes less and less interesting to produce even more of the same. However, we do not need to worry about the future of content, for after all there is a content explosion!” That explosion is driven by machine-based text production, along the lines of the model found for example in Andrew C. Bulhak’s “Postmodernism Generator” (1996). This was a reaction to the “Alan Sokal Hoax” – a parody of post-modernist academic texts, which was taken seriously and printed in 1996. The programme4, which was originally called “Dada Engine” and which is still available on the Internet, generates meaningless texts that nonetheless appear genuine – random content, produced by a computer.

Does “uncreative practice”, directed against industrially manufactured literature churned out in Creative Writing courses, offer a way out of commercialisation practice in the sense of “Copyleft”? Does it fall more within the ambit of Net Art, as presented in exhibitions such as Connect (Zürich, 2011) or publications like art&cultures numérique(s) (2012)? Or does conceptual writing lead to a new level of artistic digital practice, which also shows how obsolete the fixation on technical means is? “Technology becomes invisible when we really start to use it in an interesting way”, Goldsmith replies. “It strikes me that Net Art and E-poetry have been more of a focus for programmers than for artists. In this respect programmers have made important advances by finding out the capabilities of machines. However, almost no-one ever took this seriously as art. Nowadays production by machines and the production of text seem to be inextricably linked, to such an extent that Christian Bök forecasts that in the future poets will no longer be able to write unless they know several programming languages.”

The discovery of written material in the fine arts is accompanied by a growing awareness of the way in which writing is conditioned by code, as already articulated at the start of the new millennium by theorists such as Matthew Fuller or Lev Manovich in Software takes command.5 Naturally without any literary ambitions, as Goldsmith emphasises. Nevertheless, a new challenge emerged for the presentation of works, which correspondingly also reflected on the hardware and software conditions of their production. How can this be transposed into exhibition space in relation to ways of dealing with writing, which unavoidably entails dealing with symbolically generated meaning? Perhaps through “conceptual curating”?

“Curating is in a sense always conceptual”, Mathieu Copeland explains. “An exhibition cannot come into being without the artworks that enable it to exist, but nevertheless an exhibition is quite definitely more than the artworks or the institution that enables it – its materiality is of a radically different nature. Curating signifies creating the abstract structures that bring about an exhibition’s existence. However, irrespective of the question of conceptual curating, an exhibition should rather be seen as a “choreographed polyphony” – both in the sense of a multiplicity of voices speaking but even more so in terms in the way in which its orchestration in space reveals the physical presence and memory of what it makes possible to experience, for a particular segment of time and evolving out of a particular script.”

This work is consequently anything but “dematerialised”. Instead it emphasises – as Goldsmith’s writing does too – the enactment of the corporeal, performative qualities inherent in each text and each image, as Nancy Spero demonstrated in 1969, deploying a paintbrush to spell out the words “All writing is pigshit. Artaud” on a canvas. In the process, she cited Artaud. And painted an image. The drama of the text in the image was already apparent in that period: there could be no image without writing, and without the image there is nothing to read. Where is the image positioned in conceptual writing? Goldsmith’s take on this: “In the mid-20th century, concrete poetry was the sphere in which image and word collided head-on, which forced us to rethink the definition of both, and so the material qualities of language took centre-stage. Digital language can be copied, cut-and-pasted, shifted, spammed etc, which breathes new life into older ideas of linguistic materiality, drawing in the process on Saussure’s concepts of the sound-image or on the idea of ‘verbi-voco-visual’ expression developed by Joyce and the Noigandres group. In our digital world, language embodies both the conceptual and the material. In a manner akin to Duchamp’s idea of the ‘infra-mince’, words flicker back and forth between the material and conceptual realm, between signified and signifier, language and image”.

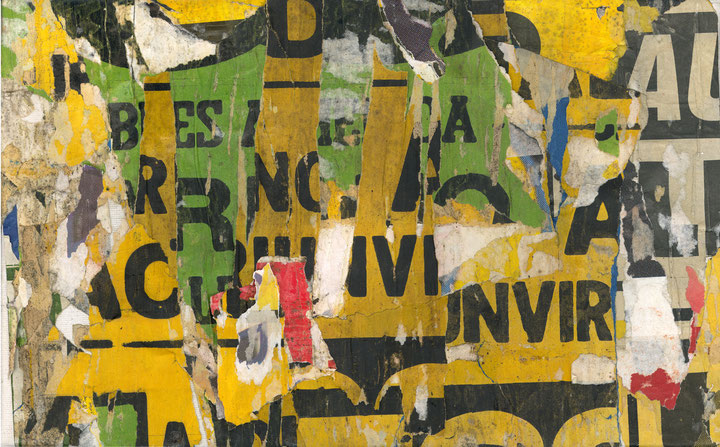

Copeland transposes this oscillation into the exhibition space, and understands curating as writing: “Harald Szeemann always referred to ‘writing exhibitions’”, he explains. “Writing is thus at both the beginning and the end of the spectrum of making exhibitions – first you write the score of an exhibition that is developing, and an exhibition is determined by the apparatus that gives it shape: the title, wall-mounted captions, explanations etc. – the written word everywhere. That was one of the reasons why for an exhibition without texts in the Jeu de Paume series I invited Jacques Villeglé to set all the texts in his socio-political font, as the exhibition texts consequently dissolve in this “illegible’ font, which means that new meaning become possible!” Villeglé, artist of torn posters, processes writing as a poet. The focus in his ripped poster works and in his alphabets is on the visual-poetic quality of writing. In this respect, Copeland’s involvement of Villeglé in a “text-free” exhibition does not repudiate the visual-material quality of writing but instead highlights it. What shape does this take when he curates purely acoustic exhibitions?

Copeland: “In the case of the series An Exhibition to Hear Read, treating artworks as written text generates a different understanding of the catalogue’s role. In the best-case scenario, the catalogue follows the thrust of the exhibition’s endeavour or calls it into question: in the worst-case scenario – which occurs much too frequently – the catalogue simply functions as a checklist of what was presented. With this series of exhibitions, which you have to hear read out, the catalogue becomes both the score of the exhibition as it emerges and a memory of it: without describing the exhibition, it instead functions more by conveying a sense of how it felt”. For Goldsmith too, the feeling is of the essence in working on text: “The art world is the wrong place for writing”, he replies in response to a question about the role he would accord to writing in an art exhibition. “The process of looking at art is a rapid one: more in-depth engagement with text in a visual space functions slowly. That is why Mathieu’s exhibitions, which must be read out loud either by actors or visitors to the museum, are so clever. He reconceptualises the role of text in an exhibition space, pulling it down from the walls to set it directly in the space, and in the process transforming dead textuality into a living drama that involves the audience”. Goldsmith provides this “living drama” with gestures: “I used to be an artist, then I became a poet and subsequently a writer. Now when asked, I simply refer to myself as a word processor”. These are the words with which Goldsmith begins the slim publication he published for Copeland’s exhibition; it reads like a manifesto, full of only marginally differentiated statements and forceful assertions, such as “The Internet destroys literature (which is a good thing)”. Here Marx’ assertion, “All that is solid melts into air”, becomes the apodictic sentence “Not only does writing melt into everything, everything also melts in writing”. Whilst claiming that he wants to foster “non-interventionist writing”, Goldsmith reduces the diversity of literary currents to commercial products, with conceptual poetry as a remedy to combat this. Is there no need for differentiation here, no respect for the singular? “The work that I made for the Jeu de Paume is actually a much more conceptual kind of text than my conceptual written works”, Goldsmith admits. “It is more like a conventional book on my intellectual universe, more in diary form and should therefore be viewed differently from my more interventionist texts. I do not always function in the same mode.”

Recently emotionality has played an increasing role in Goldsmith’s work. In Seven American Deaths and Disasters, his latest book, which takes its title from a Warhol series, he creates a montage of media reports of national tragedies, such as the assassination of John F. Kennedy or John Lennon. It is exactly the kind of narrative-historicist work he had previously aimed to undermine through the mechanical reproduction of text. Has the conceptualist a convert to the epic form now? “The book is very different from my previous works”, Goldsmith counters, “I get bored of being so boring, which is why I decided to produce something following that very method. Except that this time I have turned my lens on things that are emotional, historical and laden with suspense, rather than on fashionable, vacuous matters.”

The liberation that Copeland and Goldsmith’s practices take as their objective alludes to responsibility in dealing with writing and images, demands attention to history and each of the singular units of the texts, which, as content, are ripped out of their contexts like uncaptioned images. Neo-conceptual approaches de facto achieve something that the industrial imperative of innovation sidelines: turning the gaze back to that “pile of debris” that Laurie Anderson sung about in 1989 in The Dream Before, quoting Walter Benjamin’s “angel of history”. The angel cannot repair anything; progress blows him backwards into the future. Goldsmith and Copeland are not angels or geniuses. They remain behind on earth, rummaging in piles of debris, re-arranging in heaps what they find there. And inviting others to do likewise.

Translated by Helen Ferguson

1 Lucy R. Lippard, The Dematerialization of Art (1968), in: id.: Changing. Essays in Art Criticism. New York 1971, p. 275.

2 Ibid.

3 Ivan Illich, Im Weinberg des Textes. Als das Schriftbild der Moderne entstand. Frankfurt am Main 1991.

4 See www.elsewhere.org/pomo/

5 An updated version of the text, first published in 1999, is in preparation and scheduled to appear in late 2013; http://lab.softwarestudies.com/p/softbook.html